The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Sentimental Adventures of Jimmy Bulstrode, by Marie Van Vorst This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The Sentimental Adventures of Jimmy Bulstrode Author: Marie Van Vorst Illustrator: Alonzo Kimball Release Date: October 13, 2010 [EBook #34065] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK JIMMY BULSTRODE *** Produced by Al Haines

In which he buys a Christmas tree

In which he tries to buy a portrait

In which he finds there are some things which one cannot buy

In which he makes three people happy

In which he makes nobody happy at all

In which he discards a knave and saves a queen

In which he becomes the possessor of a certain piece of property

In which he comes into his own

There was never in the world a better fellow than Jimmy Bulstrode. If he had been poorer his generosities would have ruined him over and over again. He was always being taken in, was the recipient of hundreds of begging letters, which he hired another soft-hearted person to read. He offended charitable organizations by never passing a beggar's outstretched hand without dropping a coin in it. He was altogether a distressingly impracticable rich person, surrounded by people who admired him for what he really was and by those who tried to squeeze him for what he was worth!

It was a general wonder to people who knew him slightly why Bulstrode had never married. The gentleman himself knew the answer perfectly, but it amused him to discuss the question in spite of the pain, as well as for the pleasure that it caused him to consider—the reason why.

Mary Falconer, the woman he loved, was the wife of a man of whom Bulstrode could only think in pitiful contempt. But, thanks to an element of chivalry in the character of the hero of this story the years, as time went on, spread back of both the woman and the man in an honorable series, of whose history neither one had any reason to be ashamed.

Nevertheless, it struck them both as rather humorous, after all, that of the three concerned her husband should be the only renegade and, notwithstanding, profit by the combined good faith of his wife and the man who loved her.

Oh, there was nothing easy in the task that Jimmy set for himself! And it did not facilitate matters that Mary Falconer scarcely ever helped him in the least! She was a beautiful woman, a tender woman, and there were times when her friend felt that she cleverly and cruelly taunted him with Puritanism and with his simple, old-fashioned ideas and crystal clearness of vision, the culte he had regarding marriage and the sacred way in which he held bonds and vows. It was no help at all to think she rebelled and jested at his reserve; that she did her best to break it—and there were times when it was a brilliant siege. But down in her heart she respected him, and as she saw around her the domestic wrecks with which the matrimonial seas are encumbered, and knew that her own craft promised to go safely through the storm, Mary Falconer more than once had been grateful to the man.

As far as Bulstrode himself was concerned, each year—there had been ten of them—he found the situation becoming more difficult and dangerous. Not only did the future appear to him impossible as things were, but he began to hate his arid past. He was sometimes led to ask, what, after all, was he getting out of his colossal sacrifice? The only reward he wanted was the woman herself, and, unless her husband died, she would never be his. Bulstrode had not found that he could solve the problem, and now and then he let it go from sheer weariness of heart.

In the face of the window of the drawing-room where Bulstrode sat on this afternoon of an especial winter's day the storm cast wreaths of snow that clung and froze, or dropped like feathers down against the sill. The gentleman had his predilections even in New York, and in the open fireplace the logs crumbled and disintegrated to ashen caves wherein the palpitating jewels of the heat were held. Except for this old-fashioned warmth, there was none other in the room, whose white wainscoting and pillars, low ceilings and quaint chimney-piece, characterized one of those agreeably proportioned houses still to be found in lower New York around Washington Square.

Bulstrode had received about half an hour ago a letter whose qualities and suggestions were something disturbing to him:

"There is such a thing, believe me" (Mary Falconer wrote in the pages which Bulstrode opened to read for the twentieth time), "as the gloom of Christmas, Jimmy. People won't frankly own to it. They're afraid of seeming sour and crabbed. But don't you, who are so exquisitely apt to feelings—to other people's feelings,—at once confess it? It attacks the spinster in the bustling winter streets as she is elbowed by some person, exuberantly a mother, and so arrogantly laden with delicious-looking parcels that she is almost a personal Christmas tree herself. I'm confident this 'gloom of Christmas' grips the wretched little beings at toy-shop windows as they stand 'choosin'' their never-to-be-realized toys. I'm sure it haunts the vagrant and the homeless in a city fairly redolent of holly and dinners, and where the array of other people's homes is terrifying. And, my dear friend, it is so horribly subtle that no doubt it attacks others whose only grudge is that their hearths are not built for Christmas trees or the hanging of stockings. But these unfortunates are not saying anything aloud, therefore we must not pry!

"There's a jolly house-party on at the Van Schoolings'. We're to go down to-morrow to Tuxedo and pass Christmas night, and you are, of course, asked and wanted. Knowing your dread of these family feasts—possibly from just such a ghost of the gloom—I was sure you would refuse. But it's a wonderful place for a talk or two, and I shall hope you will go—will come, not even follow, but go down with me."

There was more of the letter—there always is more of women's letters. Their minds and pens are so charmingly facile; there is nothing a woman can do better than talk, except to write.

Bulstrode smoked slowly, the pages between his fingers, his thoughts travelling like wanderers towards a home from which a ban had kept them aliens. His eyes drifted to the beginning of the letter. He wasn't familiar with the homeless vagrant class. His charities to that part of the population consisted in donations to established societies, and haphazard giving called forth by a beggar's extended hand.

If anybody may be immune to the melancholy of which his friend Mrs. Falconer spoke, it should surely be this gentleman, smoking his cigar before the fire. The unopened letters—there was a pile of them—would have offered ample reason why. No one of the lot but bore some testimony to the generous heart which, beneath dinner-jacket and behind the screw-faced watch with the picture in the back of it, beat so healthy and so well.

But the bestowal of benefits, whilst it may beautify the giver, does not always transform itself into the one benefit desired and console the bestower! Bulstrode had a charming home. He was alone in it. He had his clubs where bachelors like himself, more or less infected with Christmas gloom, would be glad to greet him. He had his friends, many of them, and their home circles were complete. His, by force of circumstances, began and ended with himself, and as if triumphant to have found so tempting a victim, the gloom came and possessed Bulstrode as he sat and mused.

But the decided sadness that stole across his face bore no relation, to the season, to whose white mystery and holy beauty there was something in his boyish, kindly heart that always responded.

The sadness Mrs. Falconer's letter awakened would not sleep. What his Christmas might be...! He had only to order his motor, to call for her and drive over the ferry; to sit beside her in the train, to drive with her again across the wintry roads. He had but to see her, watch her, talk with her, share with her the day and evening, to have his Christmas as nearly what a feast should be as dreams could ask. The whole festival was there: joy, good-will—peace? No. Not peace for him or for her—not that; everything else, but not that. And he had been travelling for five weary months in order to make himself keep for her that peace a little longer.

Bulstrode sighed here, lifted the letter where there was more of it to his lips—held it out toward the fire as if the red jewels were to set themselves around it, thought differently, and putting it back in its envelope, thrust it in the pocket of his waistcoat.

"Ruggles," he asked the servant who had come in, "you sent the despatch to Tuxedo?"

"Yes, sir."

"There'll be later a note to send. I'll ring. Well, what is it?"

"There's a person at the door, sir, who insists on seeing you."

The servant's tone—one particularly jarring to the ears of a man who had fellowship with more than one class of his kind—made the master look sharply up. Ruggles was a new addition to the household, and Bulstrode did not like him.

"A person," Bulstrode repeated, quietly; "what sort of a person?"

"A man, sir."

"Not a gentleman? No," he nodded gently; "I see you do not think him one. Yet that he is a man is in his favor. There are some gentlemen who aren't men, you know. Let him in."

In doing so Ruggles seemed to let in the night. Bulstrode had, in the warmth of his fragrant room, forgotten that outside was the wintry dark. Ruggles, in letting the man in, had the air of thrusting him in, and shut the door behind the visitor with a click.

The creature himself let in the cold; he seemed made of it. The snow clung to his shoulders; his shoes, tied up with strings, were encrusted with it. His coat, buttoned to his chin, frayed at the cuffs and edges, was thin and weather-stained. He had a pale face, a royal growth of beard—this was all Bulstrode had time to remark. He rose.

"My servant says you want to see me. Come near the fire, won't you?"

The visitor did not stir. Bewildered in the warmth of the room, he stood far back on the edge of the thick rug. To all appearances he was a bit of driftwood from the streets, one of the usual vagrant class who haunt the saloons and park and steer from lockup to night-lodging, until they finally steer themselves entirely off the face of history, and the potter's field gathers them in. Nothing but his entrance into this conventional room before this well-balanced member of decent society was peculiar.

As he still neither moved nor spoke, Bulstrode, approaching him, again invited: "Come near the fire, won't you? and when you are warm tell me what I can do for you."

"It's the storm," murmured the man, and a half-human look came across his face with his words. "I mean to say, it's this hellish storm that's got in my throat and lungs. I can't speak—it's so warm here. It will be better in a second. No, not near the fire; thanks—chilblains." He looked down at his poor feet.

The voice which the storm had beaten and thrashed to painful hoarseness was entirely out of keeping with the man's appearance, and in intonation, accent, and language was a shock to the hearer.

"Don't stand back like that—come into the room." Bulstrode wheeled a chair briskly about. "There; sit down and drink this; it's a mild blend."

"I'm very wet," said the man. "I'll drip on the rug."

"Hang the rug!"

The tramp drained the glass given him at one swallow merely; it appeared to clear his throat and release his speech. He gathered his rags together.

"I beg pardon for forcing myself on you like this, but I fancy I needn't tell you I'm desperate—desperate!" He held out his hand; it shook like a pale ghost's. "I look it, I'm sure. I haven't eaten a meal or slept in a bed for a fortnight. I've begged work and charity. All day I've been shovelling snow, but I'm too weak to work now."

He was being led to a chair. He sank in it. "Before they sent me to the Island I decided to try a ruse. I went into a saloon and opened a directory, and I said, 'The first name I put my finger upon I'll take as good luck, and I'll go and see the person, man or woman. I opened to James Thatcher Bulstrode, 9 Washington Square." He half smiled; the pale, trembling hand was waving like a pitiful flag, a signal of distress to catch the sight of some bark that might lend aid. "So I came here. When there seemed actually to be some chance of my getting in, why, my courage failed me. I don't expect you to believe my story or to believe anything, except that I am desperate—desperate. It's below zero to-night out there—infernally cold." He took the pin out of the collar turned up around his neck and let his coat fall back. Under it Bulstrode saw he wore a thin flannel shirt. The tramp repeated to himself, as it were, "It's a bad storm."

He looked up in a dazed fashion at his host as if for acceptance of his remark. In the easy chair, half swathed in rags, pitiful in thinness, dripping from shoes and clothes water that the storm had drenched into him, he was a sorry object in the atmosphere of the well-ordered conventional room. The heat and whiskey, the famine and exposure, cast a film across his eyes and brain. He indistinctly saw his host pass into the next room and shut the door behind him.

"By Jove!" he murmured under his breath in wonder find dumb thanks for the shelter. "By Jove!" The stimulant filtered agreeably through him; more charitable than any element with which he had been lately familiar, the fire's heat began to thaw the ice in his bones. He laid his dripping hat on his knees, his thin hands folded themselves over it, his eyes closed. For hours he had shuffled about the streets to keep from freezing. At the charity organization they gave work he was too weak to do; he had not eaten a substantial meal in so long that he had forgotten the taste of food and had ceased to crave it. In the soft light of lamp and fire he fell into a doze. Bulstrode, if he had stolen softly in to look at his visitor, would have seen a man not over thirty years of age, although want and dissipation added ten to his appearance. He would have been quick to take note of the fine, delicately cut face under the disfiguring beard, and of the slender, emaciated body deformed by its rags.

Possibly he did so noiselessly come in and stand by the unconscious creature, but the sleeping vagabond, dreaming fitful, half-painful things, was ignorant of the visitor. Finally across his mind's sharp despair came a sense of warmth and comfort, and in its spell he awoke.

A servant, not the one who had thrust him into the drawing-room, but another with a friendly face, stood at his side, and in broken English asked the guest of Bulstrode to follow him; and gathering his scattered senses together and picking up his rags and what was left of himself, the creature obeyed a summons which he supposed was to hale him again into the winter streets.

It was some three hours later that Bulstrode in his dining-room entertained his singular guest.

"I have asked you to dine with me," he explained, with a certain graciousness, as if he claimed, not gave, a favor, "as I'm all alone to-night. It's Christmas eve, you know—or perhaps you've been more or less glad to forget it?"

The young man who took the chair indicated him was unrecognizable as the stranger who had staggered into 9 Washington Square three or four hours before. Turned out in spotless linen and a good suit that fitted him fairly well, shaven face save for a mustache above his lip, bathed, brushed, refreshed by nourishment and sleep and repose, he looked like one who has been in the waters, possibly a long, long time; like one who has drifted, been bruised, shattered, and beaten, but who has nevertheless drifted to shore; and in spite of his borrowed clothes, his scarred, haggard face, he looked like a gentleman, and Bulstrode from the moment he spoke had recognized him as one.

The food was a feast to the stranger, in spite of nourishment already given him by Prosper. He restrained the ferocious hunger that woke at sight and smell of the good things, forced himself not to cry out with eagerness, not to tear and grasp the eatables off the plate, not to devour like a beast. Every time he raised his eyes he met those of the butler Ruggles, and as quickly the stranger looked away. The face of the servant standing by the sideboard, back of him the white and gleaming array of the Bulstrode family silver like piles of snow, was for some reason or other not a pleasant face; the stranger did not think it so.

Once again seated in the room he had entered in his outcast state, a cup of coffee at his hand, a cigar between his lips, the agreeable atmosphere of the old room and its charming objects, the kindly look on the face of his host, all swam before him. Looking frankly at Bulstrode, he said, not without grace of manner:

"I give it up. I can't—it's not to be made out or understood..."

"Do you," interrupted the other, "feel equal to talking a little: to telling me how it happens that you are wandering, as you seem to be? For from the moment you first spoke——"

The young man nodded. "I'm a gentleman. It's worse somehow—I don't know why, but it is."

Bulstrode thought out for him: "It's like remembering agreeable places to which you feel you will never return. Only," he quickly offered, "in your case you must, you know, go back."

"No," said the young man, quietly.

There was so much entire renunciation in what he said that the other could not press it.

"Better still, you can then go on?"

The vagrant looked at his companion as if to say: "Since I've known you—seen you—I have thought that I might." But he said nothing more, and Bulstrode, reading a diffidence which did not displease him, finished:

"You shall go on, and I'll help you."

The stranger bowed his head, and the wine sent the color up until his cheeks took the flush of health. Remaining a little bent over, his eyes on his feet clad in Bulstrode's shoes, he said:

"I'm an Englishman. My family is everything that's decent and all that, you know, and proud. We've first-rate traditions. I'm a younger son, and I've always been a thorn in the family's side. I've been a sort of vagabond from the first, but never as bad as they thought or believed."

He paused. His recital was painful to him. Bulstrode waited, then knocking off the ash from his cigar, urged:

"Tell me about it, tell me frankly; it will, you see, be a relief. We can do better that way—if I know."

The stranger looked up at him quickly, then leaning forward in his chair, talked as it were to the carpet, and rapidly:

"It's just a year ago. I'd been going it rather hard and got into trouble more or less—lost at cards and the races, and been running up a lot of bills. My father was awfully down on me. I'd gone home for the holidays and had a talk with my father and asked him to pay up for me just this once more. He refused, and we got very angry, both of us, and separated in a rage. The house was full of people—a Christmas ball and a tree. My father had, so it happened, quite a lot of money in the house. I knew where it was—I had seen him count it and put it away. That night for some reason the whole thing sickened me, in the mess I was in, and I left and went up to London without even saying good-by. In the course of the week my brother came and found me drunk in my rooms. It seems that the money had been taken from my father's safe, and they accused me."

"But," interrupted Bulstrode, eagerly, "it was a simple thing to exculpate yourself."

Ignoring his remark, the other continued: "I have never seen my father since that night."

No amount of former deception can persuade a man that he is a lame judge of character. The young Englishman's emaciated face, where eyes spoiled by dissipation looked out at his companion, was to this impulsive reader of humanity a good face. Bulstrode, however, saw what he wanted to see in most people. Given a chance to study them, or rather further to know them intimately, he might indeed have ended by finding in some cases a few of the imagined qualities. Here misery was evident, degradation as well, timidity, and hesitation,—but honesty? Bulstrode fancied that its characters were not effaced, and he helped the recital:

"Since you so left your people?"

"The steady go down!" acknowledged the other. "I worked my passage to the States on a liner—I stoked..."

"Any chap," encouraged the gentleman, "who can do that can pull himself, I should say, out of a worse hole."

"There's scarcely a bad habit I haven't had down in the hole with me," confessed the other, "and they've held me there."

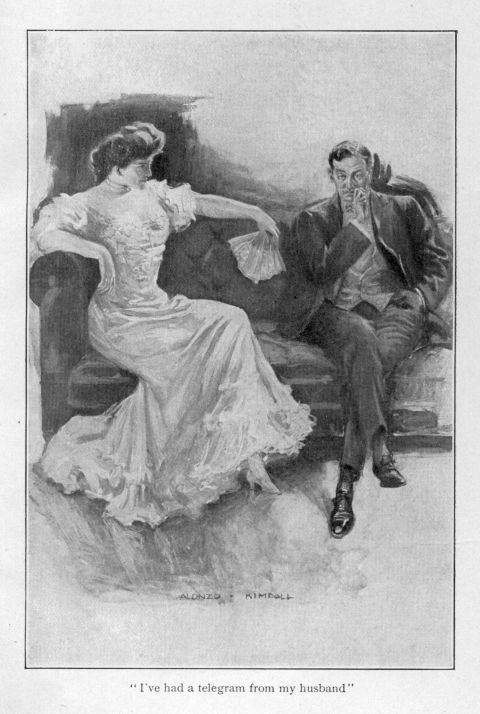

They both remained for a few seconds without speaking, and the host's eyes wandered to where, over his mantel-shelf, in a great gold frame was the portrait of a lady done by Baker. A quaint young lady in her early teens, with bare arms and frilled frock. She had Bulstrode's eyes. By her side was the black muzzle of a great hound, on whose head the little hand rested. Under the picture, from a silver bowl of roses, came a fragrance that filled the room, and, close by stood a photograph of another lady, very modern, very mocking, and very lovely.

Bulstrode, delicately drawing inferences from the influences in his life, and, if not consciously grateful, reflecting them charmingly, broke the silence:

"You must have formed some plan or other in your mind when you came to my door? What, in the event of your being received, did you intend to ask me to do?"

The stranger lifted his head and his response was irrelevant: "It seems a hundred years since I stood there in that storm and your man pulled me in. I haven't seen a place like this for long, not the inside of decent houses. When I left the ship I managed to get down with a chap as far as Florida, where he had an orange-plantation, but the venture fell through. I fancy the rest is as well forgotten. When I came in here to-night I intended to ask you for a Christmas gift of money, and I should have gone out and drunk myself to hell."

"You spoke"—Bulstrode fetched him back—"of your father and your brother; was there no one else?"

The younger man looked up without reply.

"There has been, then, no more kindly influence in your life—no sister—no woman?"

Bulstrode brought out the words; in his judgment they meant so very much. He saw a change cross the other's face.

"I fancy there are not many men who haven't had a woman in their lives for good or bad," he said, with a short laugh.

"Well," urged the gentleman, gently, "and for what was this woman?"

As if he repelled the insistence, the young fellow stammered:

"I say, this putting a fellow on the rack——"

But Bulstrode leaned forward in his chair and rested his hand on his companion's knee and pleaded:

"Speak out frankly—frankly—I believe I shall understand; it will free your heart to speak. This influence which to a man should be the best—the best—what was it to you?" Bulstrode sat back and waited, and the other man seemed quite lost in melancholy meditations for some few seconds. Then Bulstrode put it: "For a young man, no matter how wild, to leave his home under the misapprehension you claim:—for him to make no effort to reinstate himself: with no attempt at justice: for him to become a wanderer—there must be an extraordinary reason, almost an improbable one——"

"I don't ask you to hear," said the vagrant, quickly.

"I wish to do so. It would have been a simple matter to exculpate yourself—you had not the funds in your possession, had never had them. You took no means to clear yourself?"

"None."

Bulstrode looked hard at the face his care had revealed to him: the deep eyes, the neck, chin, the sensitive mouth—there was a certain distinction about him in his borrowed clothes.

"Where is the woman now?"

"She married my brother—she is Lady Waring—my name," tardily introduced the stranger, "is Cecil Waring."

Bulstrode bowed. "Tell me something of her, in a word—in a word."

"Well, she is always clever," said the young man, slowly, "always very beautiful, and then very poor."

"Yes," nodded Bulstrode.

"She is like the rest of us—one of a fast wild set—a——"

"A gambler?" Bulstrode helped the description.

"She played," acknowledged the young man, "as the rest do—bridge."

"Were you engaged to her, Waring?"

"Yes," he slowly acknowledged, as if each word hurt him.

"And did she believe you guilty?"

"I think," said the other, with an inscrutable expression, "she could not have done so."

"But she let you go under suspicion?"

"Yes."

"Without a word of good faith, of comfort?"

"Yes."

"Did she know of your embarrassments?"

"Too well."

"You tell me she was poor and—possibly she had embarrassments of her own?"

"Possibly."

Bulstrode came over to him.

"Was she at the Christmas ball that night?"

The young man rose as well, his eyes on his questioner's; the color had all left his face—he appeared fascinated—then he shook himself and unexpectedly laughed.

"No," he said; "oh no."

The older man bowed his head and replied, quite inaptly:

"I understand!"

He took a turn across the room.

The few steps brought him in front of the mantel and the photograph of the modern lady in her furs and close hat. He stood and met the fire of her mocking eyes.

"And you believe him, Jimmy!" he could hear her say in her delicious voice.

"Yes," he mentally told her, "I believe him."

"You think that to save a woman's name and honor he has become an outcast on the face of the earth ... Jimmy!"

He still gently replied to her:

"Men who love, you know, have but one code—the woman and honor."

Still mocking, but gentle as would have been the touch of the roses in the bowl near the photograph, her voice told him,

"Then he's worth saving, Jimmy."

Worth saving ... he agreed, and turned to his guest. In doing so he saw that Ruggles had come into the drawing-room to remove the coffee-tray.

"Beg pardon, sir, but you mentioned there would be a letter to send shortly?"

"By Jove! so I did!" exclaimed Bulstrode. "I beg your pardon; will you excuse me while I write a line at the desk?" The line was an order to the florist.

For some reason the eyes of the Englishman had not quitted the butler's face, and Ruggles, with cold insolence, had stared at him in turn. Waring, albeit in another man's clothes, fed and seated before a friendly hearth, and once again within the pale of his own class, had regained something of his natural air and feeling of superiority. He resented the servant's insolence, and his face was angrily flushed as Bulstrode gave his orders, and the man left the room.

"I must go away," he said, rather brusquely. "I can never thank you for what you have done. I feel as if I had been in a dream."

"Sit down." His companion ignored his words. "Sit down."

"It's late."

"For what, my friend?"

"I must find some place to sleep."

"You have found it," gently smiled Bulstrode. "Your room is prepared for you here." Then he interrupted: "No thanks—no thanks. If what you tell me is all I think it is, I'm proud to share my roof with you, Waring."

"Don't think well of me—don't!" blurted out the other. "You don't know what a ruined vagabond I am. When you send me out to-morrow I shall begin again; but let me tell you that although I've herded with tramps and thieves, been in the hospital and lock-up, and worked in the hell of a furnace in a ship's hold, nothing hurt me any more, not after I left England—not after those days when I waited in Liverpool for a word—for a sign—not after that, all you see the marks of now—nothing hurts now but the memory. I'm immune."

"You will feel differently—you will humanize."

"Never!" exclaimed the tramp.

"To-night," said Bulstrode, simply.

Waring looked at him curiously.

"What a wonderful man!" he half murmured. "I was led to you by fate: you have forced me to lay my soul bare to you—and now..."

"Let's look things in the face together," suggested the gentleman, practically. "I have a ranch out West. A good piece of property. It's in the hands of a clever Englishman and promises well. How would you like to go out there and start anew? He'll give you a welcome, and he's a first-rate business man. Will you go?"

Waring had with his old habit thrust his hands in his pockets. He stood well on his feet. Bulstrode remarked it. He looked meditatively down between the soles of his shoes.

"You mean to say you give me a chance—to—to——"

"Begin anew, Waring."

"I drink a great deal," said the young man.

"You will swear off."

"I've gambled away all the money I ever had."

"You will be taking care of mine, and it will be a point of honor."

"I'm under a cloud——

"Not in my eyes," said Bulstrode, stoutly.

"—which I can never clear."

Bulstrode made a dismissing gesture.

"I should want the chap out there to know the truth."

"The truth," caught his hearer, and the other as quickly interrupted:

"To know under what circumstances I left my people."

"No, that is unnecessary," said Bulstrode, firmly. "Nobody has any right to your past. I don't know his. That's the beauty of the plains—the freshness of them. It's a new start—a clean page."

Still the guest hesitated.

"I don't believe it's worth while. You see, I've batted about now so much alone, with nobody near me but the lowest sort; I've given in so long, with no care to do better, that I haven't any confidence in myself. I don't want you to see me fail, sir,—I don't want to go back on you."

Bulstrode had heard very understandingly part of the man's word, part of his excuse for his weakness.

"That's it," he said, musingly. "Butting about alone. It's that—loneliness—that's responsible for so many things."

Looking up brightly as his friend whose derelict dangerous vessel, so near to port and repair, was heading for the wide seas again, Bulstrode wondered: "If such a thing could be that some friend, not too uncongenial, could be found to go with you and stand as it were by you—some friend who knew—who comprehended——"

Waring laughed. "I haven't such a one."

"Yes," said the older gentleman, "you have, and he will stand by you. I'll go West with you myself to-morrow—on Christmas day. I need a change. I want to get away for a little time."

Waring drew back a step, for Bulstrode had risen. Cold Anglo-Saxon as he was, the unprecedented miracle this gentleman presented made him seem almost lunatic. He stared blankly.

"It's simpler than it looks." Bulstrode attempted conventionally to shear it of a little of its eccentricity. "There's every reason why I should look after my property out there. I've never seen it at all."

"I'm not worth such a goodness," Waring faltered, earnestly,—"not worth it."

"You will be."

"Don't hope it."

"I believe it," smiled the gentleman; "and at all events I'll stand by you till you are—if you'll say the word."

Waring, whose lips were trembling, repeated vaguely, "The word?"

"Well," replied Bulstrode, "you might say those—they're as good any—will you stand by me——?"

Making the first hearty spontaneous gesture he had shown, the young man seized the other's outstretched hand. "Yes," he breathed; "by Heaven! I will!"

It was past midnight when Bulstrode, pushing open the curtains of his bedroom, looked out on the frozen world of Washington Square, where of tree and arch not an outline was visible under the disguising snow; and above, in the sky swept clear of clouds by the strongest of winds, rode the round full disk of the Christmas moon.

The adoption of a vagrant, the quixotic decision he had taken to leave New York on Christmas day, the plain facts of the outrageous folly his impulsiveness led him to contemplate, had relegated his more worldly plans to the background. Laying aside his waistcoat, he took out the letter in whose contents he had been absorbed when Cecil Waring crossed the threshold of his drawing-room.

Well ... as he re-read at leisure her delightful plan for Christmas day, he sighed that he could not do for them both better than to go two thousand miles away! "Waring thinks himself a vagrant—and so, poor chap, he has been; but there are vagrants of another kind." Jimmy reflected he felt himself to be one of these others, and was led to speculate if there were many outcasts like himself, and what ultimately, if their courage was sufficient to keep them banished to the end, would be the reward?

"Since," he reflected, "there's only one thing I desire—and it's the one thing forbidden—I fail sometimes to quite puzzle it out!"

He had finished his preparations for the night and was about to turn out the light, when, with his hand on the electric button, he paused, for he distinctly heard from downstairs what sounded like a call—a cry.

Taking his revolver from the top drawer, he went into the hall, to feel a draft of icy air blow up the staircase, to see over the balusters the open door of the dining-room and light within it, and to hear more clearly the sounds that had come to him through closed doors declare themselves to be scuffling—struggling—the half-cry of a muffled voice—a fall, then Bulstrode started.

"I'm coming," he declared, and ran down the stairs like a boy.

On the dining-room floor, close to the window wide open to the icy night, lay a man's form, and over him bent another man cruelly, with all the animus of a bird of prey.

The under man was Ruggles, Bulstrode's butler, his eyes starting from their sockets, his mouth open, his color livid; he couldn't have called out, for the other man had seized his necktie, twisted it tight as a tourniquet around the man's gullet, and so kneeling with one knee on his chest, Waring held the big man under.

"I say," panted the young man, "can you lend a hand, sir? I've got him, but I'm not strong enough to keep him."

Bulstrode thought his servant's eyes rolled appealingly at him. He cocked his revolver, holding it quietly, and asked coolly:

"What's the matter with him that he needs to be kept?"

"Would you sit on his chest, Mr. Bulstrode?"

"No," said that gentleman. "I'll cover him so. What's the truth?"

"I heard a queer noise," panted the Englishman, "and came out to see what it was, and this fellow was just getting through the window. There was another chap outside, but he got away. I caught this one from the back, otherwise I could never have thrown him."

"You're throttling him."

"He deserves it."

"Let him up."

"Mr. Bulstrode...!"

"Yes," said that gentleman, decidedly, "let him up."

But Ruggles, released from the hand whose knuckles had ground themselves into his windpipe, could not at once rise. The breath was out of him, for he had been heavily struck in the stomach by a blow from the fist of a man whose training in sport had delightfully returned at need.

Ruggles began to breathe like a porpoise, to grunt and pant and roll over. He staggered to his feet, and with a string of imprecations raised his fist at Waring, but as Bulstrode's revolver was entirely ready to answer at command, he did not venture to leave the spot where he stood.

"Now," said his master, "when you get your tongue your story will be just the same as Mr. Waring's. You found him getting away with the silver. The probabilities are all with you, Ruggles. The police will be here in just about five minutes. Ten to one the guilty man is known to the officers. Now there's an overcoat and hat on the hat-rack in the hall. I give both of you time to get away. There's the front door and the window—which, by the way, you would better shut, Waring, as it's a cold morning."

Neither man moved. Without removing his eyes from the butler or uncovering him, Bulstrode, by means of the messenger-call to the right of the window, summoned the police. The metallic click of the button sounded loud in the room.

Ruggles shook his great hand high in air.

"I'd—I'd——"

"Never mind that," interrupted the householder. "The man who's going had better take his chance. There's one minute lost."

During the next half-second the modern philanthropist breathed in suspense. It was so on the cards that he might be obliged to apologize to his antipathetic butler and find himself sentimentally sold by Waring!

But Ruggles it was who with a parting oath stepped to the door—accelerating his pace as the daze began to pass a little from his brain, and snatched the hat and coat, unlocked the front door, opened it, looked quickly up and down the white streets, and then without a word cut down the steps and across Washington Square, slowly at first, and then on a run.

Bulstrode turned to his visitor.

"Come," he said, "let's go up to bed."

"But," stammered the young man, "you're never going to let him go like that?"

"Yes, I am," confessed the unpractical gentleman. "I couldn't send a man to jail on Christmas day."

"But the police——?"

"I shall tell them out of my window that it was a false alarm."

Bulstrode shut and locked his door, and turning to Waring, laughed delightedly.

"I must tell you that when he let you in last night Ruggles did not think you were a gentleman. He must have found out this morning that you were very much of a man. It's astonishing where you got your strength, though. He'd make two of you, and you're not fit in any way."

He looked ghastly enough as Bulstrode spoke, and the gentleman put his arm under the Englishman's. "I'll ring for the servants and have some coffee made and fetched to your room. Lean on me." He helped the vagabond upstairs.

The New Yorker, whose sentimental follies were certainly a menace to public safety and a premium to begging and vagabondage and crime, slept well and late, and was awakened finally by the keen, bright ringing of the telephone at his side. As he took up the receiver his whole face illumined.

"Merry Christmas, Jimmy!"

.......

"What wonderful roses! Thanks a thousand times!"

.......

"But of course I knew! No other man in New York is sentimental enough to have a woman awakened at eight o'clock by a bunch of flowers!"

.......

"Forgive you!" (It was clear that she did.)

.......

"Jimmy, what a day for Tuxedo, and what a shame I can't go!"

.......

"You weren't going! You mean to say that you had refused?"

.......

"I don't understand—it's the connection—West?"

"Why, ranches look after themselves. They always do. They go right on. You don't mean it, on Christmas day!"

.......

"I shouldn't care for your reasons. They're sure to be ridiculous—unpractical—unnecessary—don't tell them to me."

There was a pause, and then the voice, which had undergone a slight change said:

"Jack's ill again ... that's why I couldn't go to Tuxedo. I shall pass the day here in town. I called up to tell you this—and to suggest—but since you're going West..."

Falconer's illnesses! How well Bulstrode knew them, and how well he could see her alone in the familiar little drawing-room by a hearth not built for a Christmas tree! He had promised Waring, "I'll stand by you." It was a kind of vow—a real vow, and the poor tramp had lived up to his.

"Jimmy." There was a note he had never heard before; if a tone can be a tear, it was one.

He interrupted her.

.......

"How dear of you!"

.......

"But I haven't any Christmas tree!"

.......

"You'll fetch one? How dear of you! We'll trim it—with your roses—make it bloom. Come early and help me dress the tree."

Two hours later he opened the door into his breakfast-room with the guiltiness of a truant boy. He wore culprit shame written all over his face, and the young man who stood waiting for him in the window might almost have read his friend's dejection in his embarrassed face.

But Waring came eagerly forward, answered the season's greetings, and said quickly:

"Are you still in the same mind about the West, Mr. Bulstrode?"

(Poor Bulstrode!)

"I mean to say, sir, if you still feel like giving me this chance, I've a favor to ask. Would you let me go alone?"

Bulstrode gasped.

"Since last night a lot has happened to me, not only since you've befriended me, but since I tussled with that fellow here. I'd like a chance to see what I can do alone. If you, as you so generously plan, go with me, I shall feel watched—protected. It will weaken me more than anything else. I suppose I shall go all to pieces, but I'd like to try my strength. If I could suddenly master that chap with my fists after months of dissipation——"

Bulstrode finished for him:

"You can master the rest."

"Don't give me any extra money," pleaded the tramp, as if he foresaw his friend's impulse. "Pay my ticket out West, if you will, and write to the man who is there, and I'll start in."

Bulstrode beamed on him.

"You're a man," he assured him—"a man."

"I may become one."

"You're a fine fellow."

"You'll trust me, then?"

"Implicitly."

"Then let me start to-day. I'm reckless—let me get away. I may get off at the first station and pawn my clothes and drink and drink to a lower hell than before—but let me try alone."

"You shall go alone—and go to-day."

Prosper came in with the coffee; he, too, was beaming, and the servants below-stairs were all agog. Waring was a hero.

"Prosper," said his master, in French, "will you, after you have served breakfast, go out to the market quarters and see if you can discover for me a medium-sized, very well-proportioned little Christmas tree? Fetch it home with you."

Waring smiled faintly.

Bulstrode smiled too, and more comprehendingly, and Prosper smiled and said:

"Mais certainement, monsieur."

Bulstrode was extremely fond of travel, and every now and then treated himself to a season in London or Paris, and in the May following his adventure with Waring he saw, from his apartments in the Hôtel Ritz, from Boulevard, Bois, and the Champs Elysées, as much of the maddeningly delicious Parisian springtime "as was good for him at his age," so he said! It gave the feeling that he was a mere boy, and with buoyant sensations astir in him, life had begun over again.

Any morning between eleven and twelve Bulstrode might have been seen in the Bois de Boulogne briskly walking along the Avenue des Acacias, his well-filled chest thrown out, his step light and assured; cane in hand, a boutonnière tinging the lapel of his coat; immaculate and fresh as a rose, he exhaled good-humor, kindliness, and well-being.

From their traps and motors charming women bowed and smiled, the fine fleur and the beau monde greeted him cordially.

"Regardez moi ce bon Bulstrode qui se promene," if it were a Frenchman, or, "There's dear old Jimmy Bulstrode!" if he were recognized by a compatriot.

Bulstrode was rather slight of build, yet with an evident strength of body that indicated a familiarity with exercise, a healthful habit of sport and activity. His eyes, clear-sighted and strong, looked through the medium of no glass happily and naïvely on the world. Many years before his hair had begun to turn gray, and had not nearly finished the process; it grew thickly, and was quite dark about his ears and on his brow. Having gained experience and kept his youth, he was as rare and delightful as fine wine—as inspiring as spring. It was his heart (Mrs. Falconer said) that made him so, his good, gentle, generous heart!—and she should know. His fastidiousness in point of dress, and his good taste kept him close to elegance of attire.

"You turn yourself out, Jimmy, on every occasion," she had said, "as if you were on the point of meeting the woman you loved." And Bulstrode had replied that such consistent hopefulness should certainly be ultimately rewarded.

He gave the impression of a man who in his youth starts out to take a long and pleasant journey and finds the route easy, the taverns agreeable, and the scenes all the guide-book promised. Midway—(he had turned the page of forty)—midway, pausing to look back, Bulstrode saw the experiences of his travels in their sunny valleys, full of goodly memories, and the future, to his sweet hopefulness, promised to be a pleasant journey to the end.

During the time that he spent in Paris every pet charity in the American colony took advantage of the philanthropic Mr. Bulstrode's passing through the city, and came to him to be set upon its feet, and every pretty woman with an interest, hobby, or scheme came as well to this generous millionaire, told him about her fad and went away with a donation.

One ravishing May morning Bulstrode, taking his usual constitutional in the Bois, paused at the end of the Avenue des Acacias to find it deserted and attractively quiet; he sat down on a little bench the more reposefully to enjoy the day and time.

There are, fortunately, certain things which, unlike money, can be shared only with certain people; and Bulstrode felt that the pleasure of this spring day, the charm of the opposite wood-glades into which he meditatively looked, the tranquil as well as the buoyant joy of life, were among those personal things so delightful when shared—and which, if too long enjoyed alone, bring (let it be scarcely whispered on this bewildering May morning) something like sadness!

Before his happier mood changed his attention was attracted by a woman who came rapidly toward the avenue from a little alley at the side. He looked up quickly at the feminine creature who so aptly appeared upon his musings. She was young; her form in its simple dress assured him this. He could not see her face, for it was covered by her hands. Abruptly taking the opposite direction, she went over to a farther seat, where she sat down, and when the young girl put her arms on the back of the seat, her head upon her arms, and in the remoteness this part of the avenue offered, cried without restraint, the kind-hearted Bulstrode felt that it was too cruel to be true.

But soft-hearted though he was, the gentleman was a worldling as well, and that the outburst was a ruse more than suggested itself to him as he went over to the lovely Niobe whose abundant fair hair sunned from under her simple straw hat and from beneath whose frayed skirt showed a worn little shoe.

He spoke in French.

"Pardon, madame, but you seem in great distress."

The poor thing started violently, and as soon as she displayed her pretty tearful face the American recognized in her a compatriot. She waved him emphatically away.

"Oh, please don't notice me—don't speak to me—I didn't see that anybody was there."

"I am an American, too: can't I do anything for you—won't you let me?"

And he saw at once that she wanted to be left alone. She averted her head determinedly.

"No, no, please don't notice me. Please go away!"

He had nothing to do but to obey her, and as he reluctantly did so a smart pony-cart driven by a lady alone came briskly along and drew up, for the occupant had recognized him.

"Get in!" she rather commanded. "My dear Jimmy, how nice to find you here, and how nice to drive you at least as far as the entrance!"

As the rebuffed philanthropist accepted he cast a ruthful glance at the solitary figure on the bench.

"Do you see that poor girl over there? She's an American, and in real trouble."

"My dear Jimmy!" His companion's tone left him in no doubt as to her scepticism.

"Oh, I know, I know," he interrupted, "but she's not a fraud. She's the real thing."

They were already gayly whirling away from the sad little figure.

"Did you make her cry?"

"I? Certainly not."

"Then let the man who did wipe her tears away!"

But Bulstrode had seen the face of the girl, and he was haunted by it all day until the Bois and its bright atmosphere became only the setting for an unhappy woman, young and lovely, whom it had been impossible for him to help.

Somebody had said that Bulstrode should have his portrait done with his hands in his pockets, and Mrs. Falconer had replied, "Or rather with other people's hands in his pockets!"

The next afternoon he found himself part of a group of people who, out of charity and curiosity, patronized the Western Artists' Exhibition in the Rue Monsieur.

Having made a ridiculously generous donation to the support of this league at the request of a certain lovely lady, Bulstrode followed his generosity by a personal effort, and with not much opposition on his part permitted himself to be taken to the exhibition.

He was not, in the ultra sense of the word, a connaisseur, but he thought he knew a horror when he saw it! So he said, and on this afternoon his eyes ached and his offended taste cried out before he had patiently travelled half-way down the line of canvases.

"My dear lady," he confided sotto voce to his friend, "I feel more inclined to establish a fund for sending all these young women back to the prairies, if that's where they come from, than to aid in this slaughter of public time and taste. Why don't they stay at home—and marry?"

"That's a vulgar and limited point of view to take," his friend reproached him. "Don't you acknowledge that a woman has many careers instead of one? You seem to be thoroughly enjoying your liberty! What if I should ask you why you don't stay at home, and marry?"

Bulstrode looked at his guide comprehensively and smiled gently. His response was irrelevant. "Look at this picture! It's too dreadful for words."

"Hush, you're not a judge. Here and there there is evidence of great talent."

They had drawn up before a portrait, and poor Bulstrode caught his breath with a groan:

"It's too awful! It's crime to encourage it."

Mrs. Falconer tried to lead him on.

"Well, this is an unfortunate place to stop," she confessed. "That portrait represents more tragedy than you can see."

"It couldn't," murmured Bulstrode.

"The poor girl who did it has struggled on here for two years, living sometimes on a franc a day. Just fancy! She has been trying to get orders so that she can stay on and study. Poor thing! The people who are interested say that she's been near to desperation. She is awfully proud, and won't take any assistance but orders. You can imagine they're not besieging her! She has come to her last cent, I believe, and has to go home to Idaho."

"Let her go, my dear friend." Bulstrode was earnest. "It's the best thing she could possibly do!"

His companion put her hand on his arm.

"Please be quiet," she implored. "There she is, standing over by the door. That rather pretty girl with the disorderly blonde hair."

Bulstrode looked up—saw her—looked again, and exclaimed:

"Is that the girl? Do you know her? Present me, will you?"

"Nonsense." She detained him. "How you go from hot to cold! Why should you want to meet her, pray?"

"Oh," he evaded, "it's a curious study. I want to talk to her about art, and if you don't present me I shall speak to her without an introduction."

Not many moments later Bulstrode was cornered in a dingy little room, where tea that tasted like the infusion of a haystack was being served. He had skilfully disassociated Miss Laura Desprey from her Bohemian companions and placed her on a little divan, before which, with a teacup in his hand, he stood.

She wore the same dress, the same hat—and he did not doubt the same shoes which characterized her miserable toilet when he had surprised her childlike display of grief on a bench in the Bois. He had done quite right in speaking to her, and he thanked his stars that she did not in the least remember him.

He thought with kind humor: "No wonder she cries if she paints like that!"

But it was not in a spirit of criticism that he bent his friendly eyes on the Bohemian. He had the pleasure of seeing her plainly this time, for the window back of her admitted a generous square of light against which her blonde head framed itself, and her untidy hair was like a dusty mesh of gold. She regarded the amiable gentleman out of eyes child-like and purely blue. Under her round chin the edges of a black bow tied loosely stood out like the wings of a butterfly. Her dress was careless and poor, but she was grace in it and youth—"and what," thought Bulstrode, "has one a right to expect more of any woman?" He remembered her boots and shuddered. He remembered the one franc a day and began his campaign.

"I want so much to meet the painter of that portrait over there," he began.

Her face lightened.

"Oh, did you like it?"

"I think it's wonderful, perfectly wonderful!"

A slow red crept up the thin contour of her cheek. She leaned forward!

"Do you really mean that?"

He said most seriously:

"Yes, I can frankly say I haven't seen a portrait in a long time which impressed me so much."

His praise was not in Latin Quarter vernacular, and coming from a Philistine, had only a certain value to the artist. But to a lonely stranded girl the words were balm. Bulstrode, in his immaculate dress, his conventional manner, was as foreign a person to the Bohemian student as if he had been an inhabitant of another planet. Her speech was brusque and quick, with a generous burr in her "rs" when she replied.

"I've studied at Julian's two years now. This was my Salon picture, but it didn't get in."

"If one can judge by those that did"—Bulstrode's tact was delightful—"you should feel honorably refused. I suppose you are at work on another portrait?"

The face which his interest had brightened clouded.

"No, I'm going home—to Idaho—I'm not painting any more."

All the tragedy to a whole-souled Latin Quarter art student that this implied was not revealed to Bulstrode, but, as it was, his sensitive kindness felt so much already that it ached. He hastened toward his goal with eagerness:

"I'm so awfully sorry! Because, do you know, I was going to ask you if you couldn't possibly paint my portrait?" It came from him on the spur of the moment. His frank eyes met hers and might have quailed at his hypocrisy, but the expression of joy on her face, eclipsing everything else, dazzled him.

She cried out impulsively:

"Oh—goodness!" so loud that one or two tea-drinkers turned about. After a second, having gained control and half as though she expected some motive she did not understand:

"But you never heard of me before to-day! I don't believe you really liked that portrait over there so very much."

With a candor that impressed her he assured her: "I give you my word of honor I've never felt quite so about any portrait before."

Here Miss Desprey had a cup of tea handed her by a vague-eyed girl who stumbled over Bulstrode in her ministrations, much to her confusion.

Laura Desprey drank her tea with avidity, put the cup down on the table near, and leaning over to her patron, exclaimed:

"I just can't believe I've got an order!"

Bulstrode affirmed smiling: "You have, and if you could arrange to stay over for it—if it would," he delicately put, "be worth your while——"

She said quietly:

"Yes, it would be worth my while."

A distrait look passed over her face for a second, and Bulstrode saw he was forgotten in, as he supposed, a painter's vision of an order and its contingent technicalities.

"I can begin at once." He lost no time. "I'm quite free."

"But—I have no studio."

"There must be studios to rent."

Yes. She knew of one; she could secure it for a month. It would take that time—she was a slow worker.

"But we haven't discussed the price." Before so much poverty and struggle—not that it was new to him, but clothed like this in beauty it was rare and appealed to him—he was embarrassed by his riches. "Now the price. I want," he meditated, "a full-length portrait, with a great deal of background, just as handsome and expensive looking as you can paint it."

He exquisitely sacrificed himself and winced at his own words, and saw her color with amusement and a little scorn, but he went on bravely:

"Now for a man like me, Miss Desprey—I am sure you will know what I mean—a man who has never been painted before—this picture will have to cost me a lot of money. You see otherwise my friends would not appreciate it."

In the vulgarian he was making himself out to be his friends would not have recognized the unpretentious Bulstrode.

"Get the place, Miss Desprey, and let me come as soon as you can. All this change of plans will give you extra expenses—I understand about that! Every time I change my rooms it costs me a fortune. Now if you will let me send you over a check for half payment on the picture, for, let us say"—he made it as large as he dared and a quarter of what he wanted. They were alone in the tea-room, the motley gathering had weeded itself out. Miss Desprey turned pale.

"No," she gasped; "I couldn't take anything like half so much for the whole thing."

Bulstrode said coldly:

"I'm afraid I must insist, Miss Desprey; I couldn't order less than a fifteen-hundred dollar portrait. It's the sum I have planned to pay when I'm painted."

"But a celebrated painter would paint it for that."

Bulstrode smiled fatuously.

"Can't a man pay for his fads? I want to be painted by the person who did that portrait over there, Miss Desprey."

In a tiny studio—the dingy chrysalis of a Bohemian art student—Bulstrode posed for his portrait.

Each morning saw him set forth from the Ritz alert and debonaire in his fastidious toilet—-saw him cross the Place Vendôme, the bridge, and lose his worldly figure in the lax nonchalant crowd of the Quarter Latin. At the end of an alley as narrow and picturesque as a lane in a colored print he knocked at a green door, and was admitted to the studio by his protégée. In another second he had assumed his prescribed position according to the pose, and Miss Desprey before her easel began the séance.

On these May days the glass roof admitted delightful gradations of glory to the commonplace atelier. A few cheap casts, a few yards of mustard-toned burlaps, some Botticelli and Manet photographs, a mangy divan, and a couple of chairs were the furnishings. It had been impossible for Bulstrode to pass indifferently the venders of flowers in the festive, brilliant streets, and great bunches of giroflé, hyacinths, and narcissi overflowed the earthenware pitchers and vases with which the studio was plentifully supplied. The soft, sharp fragrance rose above the shut-in odor of the atelier, and, while Miss Desprey worked, her patron looked at her across waves of spring perfume.

Her painting-dress, a garment of beige linen, half belted in at the waist and entirely covering her, made her to Bulstrode, from the crown of her fair hair to the tip of her old tan shoes, seem all of one color. He had taken tremendous interest in his pose, in the progress of the work. He would have looked at the portrait every few moments, but Miss Desprey refused him even a glimpse. He was to wait until all manner of strange things took place on the canvas, till "schemes and composition" were determined, "proper values" arrived at, and he listened to her glib school terms with respect and a sanguine hope that with the aid of such potent technicalities and his interest she might be able to achieve this time something short of atrocious.

He posed faithfully for Miss Desprey, and smiled at her with friendly eyes whenever he caught anything more personal than the squinting glance with which she professionally regarded him, putting him far away or fetching him near, according to her art's requirements. They talked in his rest, and he took pleasure in telling her how he enjoyed his morning walks from his hôtel, how the outdoor life delighted him, and how all the suburban gardens seemed to have been brought to Paris to glow and blossom in the venders' carts or in little baskets on the backs of women and boys, and how thoroughly well worth living he thought life in Paris was.

"There is," he finished, "nothing in the world which compares to the Paris spring-time, I believe, but I have never been West. What is spring like in Idaho?"

Miss Desprey laughed, touched her ruffled hair with painty fingers, blushed, and mused.

"Oh, it's all right, I guess. There's a trolley-line in Centreville, an electric plant and the oil works—no trees, no flowers, and the people all look alike. So you see"—she had a dazzling way of shaking her head, when her fine white teeth, her sunny dishevelled hair, her bright cheeks and eyes seemed all to flash and chime together—"so you see, spring in Centreville and Paris isn't the same thing at all! Things are beautiful everywhere," she assured him slowly as she painted, "if you're happy—and I was very unhappy in Centreville, so I thought I'd come away and try to have a career." She poured out a long stream of garance from the tube on to her palette. Bulstrode watched, fascinated.

"And here in Paris, are you—have you been happy here?"

"Oh, dear no!" she laughed; "perfectly miserable. And it used to seem as though it was cruel of the city to be so gay and happy when I couldn't join in—" Bulstrode, remembering the one franc a day and the very questionable inspiration her poor art could impart, understood; his face was full of feeling—"until," she went slowly on, "lately." She stepped behind the canvas and was lost to sight. "I've been awfully happy in Paris for the first time. I do like beautiful things—but I like beautiful people better—and you're beautiful—beautiful."

She finished with a blush and a smile.

Bulstrode grew to think nothing at all about his portrait further than fervently to hope it would not shock him beyond power to disguise. But Miss Desprey was frightfully in earnest, and worked until her eyes glowed with excitement and her cheeks burned. Strong and vigorous and (Bulstrode over and over again said) "young, so young!" she never evinced any signs of fatigue, but stood when his limbs trembled under him and looked up radiant when he was ready to cry "Grâce!" In her enthusiasm she would have given him two sittings a day, but this his worldly relations would not permit. As she painted, painted, her head on one side sometimes, sometimes thrown back, her eyes half closed, he studied her with pleasure and delight.

"What a pity she paints so dreadfully ill! What a pity she paints at all! What difference, after all, does it make what she does? She's so pretty and feminine!" She was a clinging, sweet creature, and the walk and the flower debauch he permitted himself, the long quiet hours of companionship with this lovely girl in the atelier, illumined, accentuated, and intensified Bulstrode's already fatuous appreciation of the spring in Paris.

During Bulstrode's artistic mornings there distilled itself into the studio a magic to which he was not insensitive. Whether or not it came with the flowers or with the delicate filtering of the sun through the studio light, who can say, but as he stood in his assumed position of nonchalance he was more and more charmed by his painter. The spell he naturally felt should, and for long indeed did, emanate from the slender figure, lost at times behind her canvas, and at times completely in his view.

For years Bulstrode had been the victim of hope, or rather in this case of intent, to love again—to love anew! Neither of these statements is the correct way of putting it. He tried with good faith to prove himself to be what was so generally claimed for him by his friends—susceptible; alas, he knew better!

As he meditatively studied the blonde young girl he spun for himself to its end the idea of picking her up, carrying her off, marrying her, shutting Idaho away definitely, and opening to her all that his wealth and position could of life and the world. He grew tender at the thought of her poor struggle, her insufficient art, her ambition. It fascinated him to think of playing the good fairy, of touching her gray, hard life to color and beauty, and as the beauty and the holy intimacy of home occurred to him, and marriage, his thoughts wandered as pilgrims whose feet stray back in the worn ways and find their own old footprints there, ... and after a few moments Miss Desprey was like to be farther away from his meditations than Centreville is from Paris, and the personality of the dream-woman was another. Once Miss Desprey's voice startled him out of such a reverie by bidding him, "Please take the pose, Mr. Bulstrode!" As he laughed and apologized he caught her eyes fixed on him with, as he thought, a curious expression of affection and sympathy—indeed, tears sprang to them. She reddened and went furiously back to work. She was more personal that day than she had yet been. She seemed, after having surprised his absent-mindedness, to feel that she had a right to him—quite ordered him about, and was almost petulant in her exactions of his positions.

Her work evidently advanced to her satisfaction.

As she stood elated before her easel, her hair in sunny disorder, her eyes like stars, Bulstrode was conscious there was a change in her—she was excited and tremulous. In her frayed dress, sagging at the edges, her paint-smeared apron, her slender thumb through the hole in the palette, she came over to him at the close of the sitting, started to speak, faltered, and said:

"You don't know what it means to me—all you have done. And I can't ever tell you."

"Oh, don't," he pleaded, "pray don't speak of it!"

Miss Desprey, half radiant and half troubled, turned away as if she were afraid of his eyes.

"No, I won't try to tell you. I couldn't, I don't dare," she whispered, and impulsively caught his hand and kissed it.

When he had left the studio finally it was with a bewildering sense of having kissed her hand—no, both of her hands! but one held her palette and he couldn't have kissed that one without having got paint on his nose—perhaps he had! He was not at peace.

That same night a telegram brought him news to the effect that Miss Desprey was ill and would not expect him to pose the following day; and relieved that it was not required of him to resume immediately the over-charged relations, he went back to his old habit, rudely broken into by his artistic escapade, and walked far into the Bois.

He thought with alarming persistency of Miss Desprey. He was chivalrous with women, old-fashioned and clean-minded and straight-lived. In the greatest, in the only passion of his life, he had been a Chevalier Bayard, and he could look back upon no incidents in which he had played the part which men of the world pride themselves on playing well. Women were mysterious and wonderful to him. Because of one he approached them all with a feeling not far from worship; and he had no intention of doing a dishonorable thing. Puzzled, self-accusing—although he did not quite know of what he was guilty—he sat down as he had done several weeks before on the bench in the Avenue des Acacias. With extraordinary promptness, as if arranged by a scene-setter, a girl's figure came quickly out of a side alley. She was young—her figure betrayed it. She went quickly over to a seat and sat down. She was weeping and covered her face with her hands. Bulstrode, this time without hesitation, went directly over to her:

"My dear Miss Desprey——"

She sprang up and displayed a face disfigured with weeping.

"You!" she exclaimed with something like terror. "Oh, Mr. Bulstrode!"

Her words shuddered in sobs.

"Don't stay here! Why did you come? Please go—please."

Bulstrode sat down beside her and took her hands.

"I'm not going away—not until I know what your trouble is. You were in distress when I first saw you here and you wouldn't let me help you then. Now you can't refuse me. What is it?"

He found she was clinging to his hands as she found voice enough to say:

"No, I can't tell you. I couldn't ever tell you. It's not the same trouble, it's a new one and worse. I guess it's the worst thing in the world."

Bulstrode was pitiless:

"One that has come lately to you?"

"Oh, yes!"

She was weeping more quietly now.

"Please leave me: please go, Mr. Bulstrode."

"A trouble with which I have had anything to do?"

She waited a long time, then faintly breathed:

"Yes."

The hand he firmly held was gloveless and cold—before he could say anything further she drew it away from him and cried:

"Oh, I ought never to have let you guess! You were so good and kind, you meant to help me so, but it's been the worst help of all, only you couldn't know that," she pleaded for him. "Please forgive me if I seem ungrateful, but if I had known that I was going to suffer like this I would have wished never to see you in the world."

Bulstrode was trying to speak, but she wouldn't let him:

"I never can see you again. Never! You mustn't come any more."

But here she half caught her breath and sobbed with what seemed naïve and adorable daring:

"Unless you can help me through, Mr. Bulstrode—it is your fault, after all."

If this were a virtual throwing of herself into his arms, they were all but open to her and the generous heart was all but ready "to see her through." Bulstrode was about to do, and say, the one rash and irrevocable perfect thing when at this minute fate again at the ring of the curtain opportuned. The tap, tapping, of a pony's feet was heard and a gay little cart came brightly along. Bulstrode saw it. He sprang to his feet. It was close upon them.

"You will let me come to-morrow?" he asked eagerly,

"Oh, yes," she whispered; "yes, I shall count on you. I beg you will come."

"Jimmy," said the lady severely as he accepted her invitation to get into the cart, "this is the second wicked rendezvous I have interrupted. I didn't know you were anything like this, and I've seen that girl before, but I can't remember where."

"Don't try," said Bulstrode.

"And she was crying. Of course you made her cry."

"Well," said Bulstrode desperately, "if I did, it's the first woman that has ever cried for me."

As the reason why Bulstrode had never married was again in Paris, he went up in the late afternoon to see her.

The train of visitors who showed their appreciation of her by thronging her doors had been turned away, but Bulstrode was admitted. The man told him, "Mrs. Falconer will see you, sir," by which he had the agreeably flattered feeling that she would see nobody else.

When he was opposite her the room at once dwindled, contracted, as invariably did every place in which they found themselves together, into one small circle containing himself and one woman. Mrs. Falconer said at once to Bulstrode:

"Jimmy, you're in trouble—in one of your quandaries. What useless good have you been doing, and who has been sharper than a serpent's tooth to you?"

Bulstrode's late companionship with youth had imparted to him a boyish look. His friend narrowly observed him, and her charming face clouded with one of those almost imperceptible nuances that the faces of those women wear who feel everything and by habit reveal nothing.

"I'm not a victim." Bulstrode's tone was regretful. "One might say, on the contrary, this time that I was possibly overpaid."

"Yes?"

"I haven't," he explained and regretted, "seen you for a long time."

"I've been automobiling in Touraine." Mrs. Falconer gave him no opportunity to be delinquent.

"And I," he confessed, "have been posing for my portrait. Don't," he pleaded, "laugh at me—it isn't for a miniature or a locket; it's life-size, horribly life-size. I've had to stand, off and on with the rests, three hours a day, and I've done so every day for three weeks."

Mrs. Falconer regarded him with indulgent amusement.

"It's your fault—you took me to see those awful school-girl paintings and pointed out that poor young creature to me." And he was interrupted by her exclamation:

"Oh, how dear of you, Jimmy! how sweet and kind and ridiculous! It won't be fit to be seen."

"Oh, never mind that," he waved; "no one need see it. I haven't—she won't let me."

He had accepted a cup of tea from the lady's hand; he drank it off and sat down, holding the empty cup as if he held his fate.

"Tell me," she urged, "all about it. It was just like you—any other man would have found means to show charity, but you have shown unselfish goodness, and that's the rarest thing in the world. Fancy posing every day! How ghastly and how wonderful of you!"

"No," he said slowly, "it wasn't any of these things. I wanted to do it. It amused me at first, you see. But now I am a little annoyed—rather bothered to tell the truth—He met her eyes with almost an appeal in his. Mrs. Falconer was in kindness bound to help him.

"Bothered? How, pray? With what part of it? You're not chivalrous about it, are you? You're not by the way of feeling that you have compromised her by posing?"

"Oh, no, no," he hurried; "but I do feel, and I am frank to acknowledge, that it was a mistake. Because—do you know—that for some absurd reason I am afraid she has become fond of me." He blushed like a boy. Mrs. Falconer said coldly:

"Yes? Well, what of it?"

"This—" Bulstrode's voice was quiet and determined—"if I am right I shall marry her."

Mrs. Falconer had the advantage over most women of completely understanding the man with whom she dealt. She knew that to attempt to turn from its just and generous source any intent of Mr. Bulstrode would have been as futile as to attempt to turn a river from its parent fountain.

"You're quixotic, I know, but you're not demented, and you won't certainly marry this nobody—whose fancies or love-affairs have not the least importance. You won't ever see her again unless you are in love with her yourself."

Bulstrode interrupted her hastily:

"Oh, yes, I shall."

He got up and walked over to the window that looked down on Mrs. Falconer's trim little garden. A couple of iron chairs and a table stood under the trees. Early roses had begun to bloom in the beds whose outlines were thick and dark with heart's-ease. Beyond the iron rail of the high wall the distant rumble of Paris came to his ears. Mrs. Falconer's voice behind him said:

"She's a very pretty girl, and young enough to be your daughter."

"No," he said quietly, "not by many years."

As he turned about and came back to the lady the room seemed to have grown darker and she to sit in the shadow. She leaned toward him, laughing:

"So you have come to announce at last the famous marriage of yours we have so often planned together."

Bulstrode stood looking down on her.

"I feel myself responsible," he said gravely. "She was going home, and by a mistaken impulse I came in and changed her plans. She is perfectly alone and perfectly poor, and I am not going to add to her perplexities. I have no one in the world to care what I do. I have no ties and no duties."

"No," said Mrs. Falconer; "you are wonderfully free."

He said vehemently:

"I am all of a sudden wonderfully miserable."

He had been in the habit for years of suddenly leaving her without any warning, and now he put out his hand and bade her good-by, and before she could detain him had made one of many brusque exits from her presence.

On the following day—a Sunday, as from his delightful apartments in the Ritz he set forth for the studio, Bulstrode bade good-by to his bachelor existence. He knew when he should next see the Place Vendôme it would be with the eyes of an engaged man. His life hereafter was to be shared by a "total stranger." So he pathetically put it, and his sentimental yearning to share everything with a lovely woman had died a sudden death.

"There's no one in the world to care a rap what I do—really," he reflected, "and in this case I have run up against it—that's the long and the short of the matter—and I shall see it through."

As he set out for Miss Desprey's along his favorite track he remarked that the gala, festive character of Paris had entirely disappeared. The season had gone back on him by several months, and the melancholy of autumn and dreary winter cast a gloom over his boyish spirits. A very slight rain was falling. Bulstrode began to feel a twinge of rheumatism in his arm and as he irritably opened his umbrella his spirits dropped beneath it and his brisk, springy walk sagged to something resembling the gait of a middle-aged gentleman. But he urged himself into a better mood, however, at the sight of a flower-shop whose delicate wares huddled appealingly close to the window. He went in and purchased an enormous bunch of—he hesitated—there were certain flowers he could not, would not send! The selection his sentimental reserve imposed therefore consisted of sweet-peas, giroflés, and a big cluster of white roses, all very girlish and virginal. His bridal offering in his hand, he took a cab and drove to the other side of the river with lead at his good heart and, he almost fancied, a lump in his throat. He paid the coachman, whose careless spirits he envied, and slowly walked down the picturesque alley of Impasse du Maine.

"There isn't a man I know—not a man in the Somerset Club—who would be as big a fool as this!"

He had more than a mind to leave the flowers on the doorstep and run. Bulstrode would have done so now that he was face to face with his quixotic folly, but his cab had been heard as well as his steps on the walk, and the door was opened by Miss Desprey herself. The girl's colorless face, her eyes spoiled with tears, and a pretty, sad dignity, which became her well, struck her friend with the sincerity and depth of her grief, and as the good gentleman shook hands with her he realized that less than ever in the world could he add a featherweight of grief to the burden of this helpless creature.

"My dearest child!" He lifted her hand to his lips.

"Oh, Mr. Bulstrode, I'm so glad you've come, I was so afraid you wouldn't—after yesterday!"

His arms were still full of white paper, roses, and sweet-peas.