Hazeley Family.

Hazeley Family.Page 23.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Hazeley Family, by A. E. Johnson This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The Hazeley Family Author: A. E. Johnson Release Date: January 23, 2011 [EBook #35045] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE HAZELEY FAMILY *** Produced by Suzanne Shell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Hazeley Family.

Hazeley Family.

THE HAZELEY FAMILY

BY

Mrs. A. E. JOHNSON

PHILADELPHIA

American Baptist Publication Society

1420 CHESTNUT STREET

THE HAZELEY FAMILY

BY

Mrs. A. E. JOHNSON

Author of Clarence and Corinne

PHILADELPHIA

AMERICAN BAPTIST PUBLICATION SOCIETY

1420 Chestnut Street

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1894, by the

AMERICAN BAPTIST PUBLICATION SOCIETY,

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| CHAPTER I. | |

| The Hazeley Home, | 5 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Flora at Home, | 15 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Ruth Rudd, | 26 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Flora's First Sunday, | 37 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| The Beginning, | 46 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Some Results, | 58 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| A Visit to Major Joe, | 67 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| More Results, | 79 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Ruth's New Home, | 89 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Lottie Piper, | 97 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Changes, | 106 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Led Away, | 117 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| In the Hospital and Out Again, | 124 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| A Chapter of Wonders, | 132 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| Going Home, | 142 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Lottie's Trials, | 151 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| More Surprises, | 162 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| A Christmas Invitation, | 171 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| A Homely Wedding, | 180 |

SIXTEEN-YEAR-OLD Flora Hazeley stood by the table in the dingy little dining room, looking down earnestly and thoughtfully at a shapely, yellow sweet potato.

It was only a potato, but the sight of it brought to its owner, not only a crowd of pleasant memories, but a number of unpleasant anticipations. Hence, the earnest, thoughtful expression on her young face.

Flora was the only daughter. She had two brothers, one older and one younger than herself, Harry and Alec, aged respectively, eighteen and thirteen. The mother was of an easy-going, careless disposition, and seemed indifferent to the management of her household. Especially did she dislike responsibility of any kind. She was well pleased, therefore, to receive one day a letter from[6] her sister, Mrs. Graham, a childless widow, offering to take Flora, who was then just five years old, promising to rear her as if she had been her own daughter.

Mrs. Graham was well off. In her case this meant that she lived in a pretty home of her own, with a nice income, not only supporting herself in comfort, but permitting her to provide a home for her elder sister for many years, who had entire charge of the housekeeping. This sister, Mrs. Sarah Martin, was also a widow and childless. The resemblance went no further, for they differed, not only in manner, but opinions, thoughts, and character.

Mrs. Graham, after a great deal of careful thought, had come to the conclusion to adopt her little niece. In fact she had often thought it over ever since the child first began to walk, and call her by name. She was a sensible woman, and it always annoyed her when she would visit her sister to see the careless way in which the children were being trained. Seeing this, she had long wished to take and train Flora according to her own idea of what constituted the education of a girl.

"It will be so much worse for her than for the boys," she had said one day to Mrs. Martin. "I do dislike to[7] see such a bright little child brought up to be good for nothing; and that is just the way in which it will be, if I do not take charge of her myself."

The latter clause was intended to draw indirectly from her sister an opinion of such a proceeding, for Mrs. Martin was by no means partial to children. However, it was received with the indifferent observation:

"Esther never did have any interest in children anyhow. She never had any idea how to take care of herself, much less anybody else," to which was added a remark to the effect that if her sister Bertha chose to burden herself with a troublesome child, she was sure she had nothing to do with the matter, and did not intend to have.

Mrs. Graham was rather surprised to have her suggestion received so coolly. She had expected a great deal of trouble in getting Sarah to consent, even provisionally. She was very glad to meet no more serious opposition, for, although she had fully decided in her own mind regarding the matter, yet her peace-loving nature dreaded unpleasant scenes. She purposely and entirely overlooked the expression of stern determination in the sharp-featured countenance of her sister, and[8] forthwith resolved to send for Flora without further loss of time.

Thus it was that Flora Hazeley changed homes. She was not legally adopted by her aunt, but was simply taken with the understanding she would be returned to her parents in case Mrs. Graham should in any way change her mind, or weary of her charge. This provision was inserted by Mrs. Martin, who determined, in spite of her seeming indifference, not to be ignored by her sister, upon whose bounty she considered she had a primary claim.

For eleven years Flora lived in the pretty home of her Aunt Bertha. Her time was filled by various occupations, school, caring for the flowers in the garden, and dreaming under the old peach tree, which never bore any peaches, but grew on contentedly in the farthest corner of the yard.

However, these were by no means the only ways in which Flora spent her time, for Mrs. Martin, notwithstanding her stern resolve not to have anything to do with her, had suddenly taken an equally stern determination to do her share toward "bringing sister Esther's child up properly."

[9] This was fortunate for Flora. Aunt Sarah instructed her thoroughly and carefully in the details of housekeeping, cooking, serving, washing, in fact, everything she knew herself. How fortunate it was that she learned how to do these things, Flora realized some time afterward, as Mrs. Martin had intended she should. While she was learning them, Flora's progress was due rather more to the awe she felt of her stern aunt than to the desire to excel.

Mrs. Martin was ever ready to scold and find fault. Mrs. Graham never criticised, but always had a bright smile and something pleasant to say. As a natural consequence, she was dearly loved by her niece.

Mrs. Hazeley, Flora's mother, delighted to be relieved of her troublesome little girl, settled down more contentedly than ever, to enjoy the quiet of her daughter's absence, and became daily more and more indisposed to exert herself in order to make her home attractive.

It was usually pretty quiet now, because neither of the boys stayed in the house a moment longer than necessity demanded. Mr. Hazeley was employed on the railroad, and consequently was away from home a great deal. Mrs. Hazeley did little but turn aimlessly about, making herself[10] believe that she was a very hard-working woman and then imagining herself much fatigued, found it necessary to rest often and long. She was at heart a good woman, when that organ could be reached, but possessed a weak, vacillating disposition, entirely lacking the gentle firmness of her sister, Mrs. Graham, or the uncompromising energy of Mrs. Martin.

Mr. Hazeley had long ceased to complain of his home and its management, for his words had no further effect than to bring upon himself a storm of tearful scolding, which drove him out of the house to seek more genial quarters. He was by nature a peaceable man, and when he found that neither ease nor peace could be had at home, remained there as little as possible. In fact, as Mrs. Hazeley's sisters had often said, "if the whole family did not go to ruin, it would not be Esther's fault."

Flora's life at her aunt's pleasant home had been a very happy one, and the time passed rapidly away. She was nearly through school, and looked eagerly forward into the future, that to her was so full of brightest hopes. It was her ambition to be of some use in the world. Just what she wanted to do, she did not know—she[11] had not yet determined; but that it was to be something great and good, she was confident, for small things did not enter into her conception of usefulness.

Aunt Bertha was her confidante for all her plans, or rather, dreams; she could do nothing without Aunt Bertha, for had not she the means? Flora felt sure nothing great could be done without money, that is, nothing she would care to do.

But, alas! Her summer sky, so promising and brilliant with hopes and indefinite plans, was suddenly overcast. Aunt Bertha was taken ill one day; the doctor said it was prostration, and he feared she might not rally. Flora was told. Her Aunt Bertha, whom she loved so dearly, and who loved her so much! Must she die? "I love her far more than my mother," she whispered to herself. This seemed very disloyal in Flora. But in truth, she had little cause to love the mother who had been so eager to relinquish her claim, and who, in all these years, had never expressed a wish to have her daughter at home.

During her sister's illness, Aunt Sarah spent her time in constant attendance upon her. She was cold, stern, and unapproachable as ever, giving the child[12] little information in regard to the sick one who had been so kind to her. She was not allowed to enter the sick room during the first of her aunt's illness, although Mrs. Graham had often asked to see her niece.

One day, just before the spirit passed away, the sick woman called her sister, and said in a weak, trembling voice:

"Sister, I suppose you know I cannot live long, and that my will is made."

Mrs. Martin silently nodded.

"Well," continued Mrs. Graham, "I have left everything to you—I thought it would be best."

Again a silent nod.

"But, Sarah, I want you to promise one thing; that you will see Flora has what she needs to carry out her plans. The dear child has so longed to carry out some of her plans. I want her to have means to make whatever she may decide upon a success. And one more thing," she continued, pausing for breath, and looking pleadingly into the face above her, "I do hope, Sarah, that you will keep Flora here with you. Do not send her back to her home. I have left all I own in your hands, and I trust to you, sister, to do what I wish."

[13] This long expression of her wishes had so taxed the fast-failing strength of the invalid, that she sank back, exhausted. No answer was expected, and Mrs. Martin was silent; and silent too, because she had not the slightest intention of doing as her sister wished. It was truly heartless; but Mrs. Martin was one of those people who do not present the harsh side of their nature in all its intensity until the reins of power are placed in their hands. So long as Mrs. Graham held the purse-strings, she acquiesced with as much grace as possible in her sister's plans. Was not the money Mrs. Graham's to do with as she pleased? It was quite a different thing, however, to feel that now everything would be in her hands to use as she chose. No matter if the donor was still looking into her face, her mind was made up that things should be ordered in the future according to her good pleasure. It was not at all her wish to burden herself with Esther's child, and forthwith she decided that back to her home Flora should go. However, she did not allow these unworthy thoughts to disturb the last moments of her tender-hearted sister, by giving expression to them. So good Mrs. Graham passed peacefully away.

[14] Flora was allowed to see her shortly before she died. The kind voice whispered words of comfort, telling her that Aunt Sarah would take care of her. These words fell unnoticed at the time upon the ear of the sobbing girl, who had been so accustomed to have Aunt Bertha think and plan for her.[15]

MRS. GRAHAM'S life had been a quiet, unobtrusive, but truly Christian one. She had neglected no opportunity to implant in her young niece a love and reverence for holy things; and now that she was about to die, she felt that she had nothing to regret, that she had left no duty unfulfilled, so far as Flora's training was concerned. It was with a heart full of peace that she commended her charge to the "One above all others" and took her leave of earth.

Flora was almost inconsolable. She had no one to comfort her, for Aunt Sarah was as distant as ever, being entirely too much occupied with plans for the future to care about Flora. Her mother came to the funeral, but neither was overjoyed to see the other after their long separation. It could scarcely be otherwise. Natural affection had never been conspicuous in the Hazeley home, and the influence of these years apart[16] had not helped matters at all. Indeed, they were little more to each other than strangers.

After they returned from the cemetery, however, Aunt Sarah informed Flora she was to return with her mother to her former, and as she deemed it, rightful home. The feelings with which the girl received this intelligence were by no means pleasant ones. But there was no use in crying or fretting about it, for when Aunt Sarah said a thing, she meant it, and could not be induced to alter her decision, even if Flora had felt inclined to ask her to do so. This she had no thought of doing, for she was not at all anxious to make her home with her cold, distant aunt.

"It is too bad!" she exclaimed, as she thought of all the bright helpful plans she and Aunt Bertha had made together, and which they had hoped to be able to carry out. "It is too bad!" she sobbed, as she bent over her trunk in her pretty little bedroom, the tears falling on the tasteful dresses, and the many loving tokens that had been given her by the dear hands now at rest beneath the unfeeling earth in the churchyard.

Mrs. Martin was surprised that Flora's mother made no objection to taking her daughter home. The truth[17] was Mrs. Hazeley had been wanting this very thing for some time. It was not, however, because of any particularly affectionate or motherly feeling toward her child; but she had been thinking that Flora, of whose ability she had heard much, would be a very great help to her in caring for the house. Thus it was that Flora returned to the home she had left eleven years before.

Just as the train was preparing to leave the station, Lottie Piper, one of Flora's friends and admirers, came running to the car, and tossed something through the open window into Flora's lap, saying hurriedly and pantingly, as she pressed the hand held out to her:

"There, Flora, take that. Don't laugh. I raised it all myself, and I want you to have it; but don't eat it! Keep it to remember me by. Good-bye," she called, as the train moved off.

Flora waved her handkerchief out of the window to Lottie, until her arm was tired. As she looked about the cars her attention was attracted by a titter from the opposite side. At first she could not understand why the girl who sat there should look at her and smile. As her neighbor gazed at her lap, Flora's eyes followed, and[18] there she saw the cause of the merriment in Lottie's parting gift—a yellow sweet potato.

At first she felt inclined to be provoked with Lottie for bringing such a thing and causing her to be laughed at. However, the remembrance of her parting words, "I raised it all myself; but don't eat it!" made her smile in spite of herself. This encouraged the girl opposite to slip over to the seat beside Flora, as Mrs. Hazeley was occupying the one in front, and the two girls, although entire strangers to each other, chatted away busily, until the train stopped at one of the stations, where the girl and her father, who sat farther back, left the car. Soon after, Flora found herself at home, Bartonville and Brinton being but a short distance apart.

This brings us to the opening of our story.

It was Lottie's potato that lay upon the table, and Flora had been wondering what to do with it. The memories it awakened were of Brinton and the many pleasant strolls and romps she had enjoyed with Lottie in her father's fields, which joined Mrs. Graham's, of Aunt Bertha herself, and much more.

"But what am I to do with the potato?" she questioned. "I am not to eat it. I don't care to, either.[19] Oh! I know, I will plant it in a jar of water and let it grow. That would please Lottie, I guess."

She soon found a jar such as she wanted, and after washing it clean and bright, filled it full of clear water, and carefully placed the potato, end up, in it, and then looked about for a suitable place for it.

"That window has a good broad seat," she said to herself; "and it is sunny, but the glass is so grimy! However, it will do. Better yet, I will open the window."

This was more easily said than done, for, although the weather was still warm—it being September—the window did not appear to have been opened for some time.

Flora struggled and pushed, and at length succeeded in opening it, making noise enough as she did so, to attract the attention of a young girl who was passing. She stopped, looking up, inquiringly.

Flora was heated with her exertions and the thought of having attracted attention, so that before she realized what she was doing, she was smiling and saying:

"This old window was very hard to raise, but I was determined to do it."

"No," said the girl, looking as if she was not quite sure that it was the right thing to say.

[20] "What is that in the jar?" she asked, as she came closer, and looked at the potato curiously, and then at Flora in a friendly way that pleased her.

"This," said Flora, patting the vegetable; "it is a potato."

"But what have you put it in there for?" persisted the girl.

"To grow, to be sure."

"Will it grow?"

"Of course it will," replied Flora, with an important air. "See! water is in this jar, and soon this potato will sprout, send roots down and leaves up, and then—and then—it will just keep on growing, you know." And Flora felt sure that she had put quite an artistic finish to her description of potato culture.

"Oh, yes," cried her new acquaintance, with an intelligent light in her eyes; "I know very well what will happen then."

"What?" asked Flora, rather dubiously.

"Why, little sweet potatoes will grow on the roots, of course."

"I—I don't think they will," said Flora, hesitatingly, not being well versed on the subject.

[21] "Yes; but they must—they always do," returned the girl, positively.

"Well, but there would be no room in the jar for potatoes to grow," said Flora.

"That's so." And the girl looked puzzled; then they both laughed, not knowing what else to do.

"What is your name?" asked Flora, by way of changing the subject, for she was a little fearful she might be asked to explain why little sweet potatoes would not grow in her jar.

"My name is Ruth Rudd," was the answer. "What is yours?"

"Flora Hazeley."

"Is it? Well, I live just back of your house, on the next street. Good-bye. I guess I will see you some other time." And she hurried away.

"She is a real nice girl," Flora thought, as she turned away from the window; "I hope I can see her again."

She stood for an instant looking about the room. It was nicely furnished, but it looked neglected and untidy, and Flora, having been so long accustomed to the attractiveness and order of her aunt's house, felt home-sick. Her loneliness came over her in a great wave of feeling,[22] and running through the kitchen, out of the door, went into the yard, which was a good-sized one, but so filled with rubbish and piles of boards, scarcely noticed through her tears, that she met with many a stumble before she reached the farther end. She wanted some quiet place in which to sit and think, as she used to do under the old peach tree at Brinton. She was sure she "could think of nothing in that house," and the best she could do was to seat herself on an old block at the very back of the yard. She felt she could think better out in the open air, under the sky, for she was a great lover of nature, and loved to look at the blue sky. The sun was under a cloud, but the air was warm and pleasant.

How different were her thoughts now from what they had been under the old peach tree! Then she had reveled in rose-colored dreams; now she was confronted by gray realities. Her thoughts went rapidly over her life since Aunt Bertha's death.

She had been here not quite a week, and she found it such a different place from the home she had so lately left, that she was almost unwilling to call it "home." But while she considered her present home not very desirable, she had given no thought to the inmates, whether or not[23] they had found in her a very desirable addition to the circle.

She was young, and she soon wearied of her sombre thoughts, which could avail her nothing, and she glanced at the houses on each side of her own. There was a marked difference. It was not in the style of the building, for hers was the most attractive. It was, however, in the general appearance, and Flora felt she would like to begin at the topmost shingle and pull her home down to the ground. But the thought came to her that then she would have no home. She knew there was no room for her with Aunt Sarah, who was, no doubt, at this very moment enjoying her absence.

"No, indeed, I do not want to live with Aunt Sarah," she thought; and then began to wonder vaguely if she had not better go to work and try to make her present home a more congenial one.

The more she thought about it, the better the idea pleased her. Just as she was endeavoring to decide upon something definite to do, she was startled by seeing a board in the fence, just behind her, pushed aside. Before she could move, a round, fat, little face was thrust through the opening, and a pair of inquisitive brown eyes were[24] fastened upon her. For a moment they looked, and then the owner squeezed through, and stood still, eyeing Flora complacently.

"Well, and who are you? and what do you mean by coming in here that way?" asked Flora, amused at the odd-looking little creature.

"I'm Jem," answered the midget, coolly; "and I didn't mean nuffing."

"Jem? I thought you were a girl," said Flora, looking at the quaint, short-waisted dress, that reached almost down to the copper toed shoes, and the funny, little, short white apron, tied just under the fat arms, which were squeezed into sleeves much too tight for them.

"So I am a girl," answered Jem, indignantly; "don't you see I've gut a napron on wif pockets in?" And she thrust her chubby little fingers into one of them.

"But you said your name was 'Jem,' and that's a boy's name," persisted Flora, enjoying her odd companion.

"'Tain't none," was the sententious reply; "it's short for 'Jemima'; that's what my really name is."

"Well, Jemima, what do you want in here?"

"Nuffing."

"Nothing? Well, that isn't in here."

[25] "There ain't anythin' else's I can see," retorted Jem, turning down the corners of her mouth very far, and looking about disdainfully.

Flora laughed outright at this, but her visitor's countenance lost none of its solemnity.

"You do not seem to admire my yard, Jem."

"Don't see anythin' to remire," retorted Jem. "You'd just ought to peep in ours," and she moved over to the fence, and pulling away the board with a triumphant air, motioned Flora to look. Flora looked, but the first thing she saw was not the yard, but the young girl with whom she had been talking not an hour since.[26]

RUTH, standing by a long wooden bench, in the neat, brick-paved yard, was engaged in watering some plants that were her especial pride.

Hearing a noise at the fence, she turned, and recognizing Flora, smiled and asked:

"Won't you come in?"

"Thank you," replied Flora, smiling in return. "I think I will."

Jem looked on wonderingly as her sister and the visitor, whom she considered her especial property, chatted.

She could not understand how they knew each other. At length, as they took no notice of her, she determined to assert herself; so, going up to Flora, she demanded:

"What do you think of my yard?"

"Oh," said Flora, recollecting for what purpose they had come, "I like it very much indeed, Jem."

"It's a pretty good yard, I think," said Jem, with[27] much emphasis on the pronoun. "Come and look at the flowers, and I'll tell you the names of them." And she drew Flora nearer the bench.

"This is a gibonia," she continued, pointing with her fat finger to the flower named.

"You mean a 'begonia,' don't you, Jem?" said Flora.

"Yes," answered Jem, without changing countenance in the least, or seeming in any way abashed; "and this is a gerangum."

"A geranium," corrected Flora. "Yes, I see."

"And this is a chipoonia," pointing to a petunia, "and—Oh, there's Pokey!" and breaking away in the midst of her explanations, she gave chase to a fat little gray kitten that just then scampered across the yard, and into the house.

"What a cute little girl Jem is," said Flora to Ruth; "is she your sister?"

"Yes, that is, she is my half-sister; her mother was not my own mother, you know."

"Oh, she is your step-mother," said Flora.

"She was," corrected Ruth; "but she has been dead ever since Jem was a little baby. My own mother died[28] when I was quite small," she added, with an elderly air.

"Who keeps house for you?" asked Flora, in surprise.

"I do," replied Ruth. "I keep house for father, and take care of Jem. She is all the company I have."

"What a smart girl you are. How old are you, Ruth?"

"I'm sixteen, but I feel ever so much older. You see, it is a great responsibility to have everything at home resting upon one," and Ruth looked very wise.

"I should think so," said Flora, thoughtfully. "I am sixteen too."

"Are you? That's nice. We ought to be good friends," returned Ruth, smiling.

"Yes, I am sure we shall be," replied Flora, earnestly. "I like you ever so much, Ruth. I am very lonely here. I know nobody in this place except my home folks."

"How strange," said Ruth, in a puzzled way. "Tell me about it."

Flora was glad to tell her story.

"You poor child!" exclaimed matronly Ruth, taking[29] her hand between both her own, and pressing it. "How sorry I am for you."

"Are you?" said Flora, laughing nervously, for she felt more like crying. "I was just feeling sorry for you."

"Sorry for me? Why?"

"Because you have to live here all alone, or almost alone, and have so many responsibilities. You must get very lonely."

"Oh, but my responsibilities keep me so busy I have no time to be lonely. Besides, I like responsibilities."

"You do? Perhaps if I had a few I wouldn't be so lonely either; but then you see I have none."

"I think you have," returned Ruth, soberly, and added, after a moment's thought, "I think you have a great many."

"What are they?"

"Your mother, and father, and brothers, and your home. You are responsible for your conduct toward your parents. It is your duty to be a good daughter. There's your home, it is your duty to make it pleasant and comfortable. And there are your brothers——"

"Oh, do stop, Ruth!" cried Flora. "You have told me enough. You talk as if you were thirty years old[30] instead of sixteen. No, no! I will not hear any more to-day about responsibilities; I have had enough for one day," and she playfully placed her hand over Ruth's lips.

"I wasn't going to say any more about them," said Ruth. "I was only going to ask you to come into the house, for I must begin to prepare our supper."

"No, thank you!" replied Flora; "I must go now; but I should like to come again soon."

"Indeed, come as often as you please; the oftener you come the better I shall like it. Come right through the fence whenever you want to; you will almost always find me here."

"Thank you," said Flora. She bade Ruth good-bye, and returned home the same way she had come, entirely unconscious of the look of disapproval with which little Jem was regarding her from the window of an upper room, whither she had retreated with her precious Pokey.

Jem felt quite slighted. Flora and Ruth had been so much occupied with each other as to forget entirely her important little self, and she determined to severely punish "Sister Ruth" for her conduct. She immediately[31] proceeded to put her determination into execution by stowing herself and Pokey away in the darkest corner under the bed, and there she remained in spite of Ruth's coaxing calls.

Ruth found her there fast asleep, when she went to look for her at teatime. Ruth was well acquainted with Jem's various modes of punishing her, and she readily guessed the cause of her little sister's present displeasure; and likewise knowing her well, she decided to let her alone until she was ready to come down. At last Jem came down while Ruth was washing the dishes. She was in perfectly good spirits, for she felt satisfied that her sister had been sufficiently punished in having been deprived of her company for so long a time. She sat down quietly and ate her supper, which had been set aside for her. She did not say anything about the events of the afternoon and neither did Ruth, who was busy thinking about Flora. Strangely enough, influenced by some unseen power, Flora was at the same moment thinking of Ruth. When our young friend entered her home, she found her father had returned in her absence. Her mother was hurrying about in an aimless, impatient way, trying to get supper and at the[32] same time set the table. These two occupations were not progressing very rapidly in her nervous hands.

Harry and Alec were both in the dining room; the former sitting by the window reading, and the latter whittling a bit of wood with his pocket-knife, and letting the chips fly and settle where they would. It was not a very inviting picture, but with Ruth's gentle face before her, and her words "It is your duty to be a good daughter" in her mind, Flora stoutly determined she would begin immediately and undertake her responsibilities in the very best way she could. With these thoughts she quietly said to her mother she would finish setting the table. It was not much to do, but she felt a great deal better in making this first effort to be of use in her home.

"What have I been thinking about not to have been doing this before? It is an actual treat to be busy," she continued to herself, as she placed the plates, cups, and saucers on the table. She did not know it, but both Harry and Alec were watching her whenever they were sure she was not looking.

The boys had not paid any attention to their sister since her return home; in fact, they both thought it a bother to have a girl about the place. Moreover, Flora had[33] made no effort to prove herself a very valuable addition to the little family. But this evening, as she moved back and forth, the neat and tasteful way in which she arranged the table, was so different from the usual careless manner, that both boys were favorably impressed. Mrs. Hazeley too, when she hurried in with the supper, gave a sigh of relief, as she noted that everything was ready. And the father, although preoccupied with his own thoughts, glanced about with a pleased look in his eyes.

Although Flora was not aware of all this, she did not fail to notice there was a difference from the ordinary meal. The boys refrained from their usual snappish behavior, the mother was less peevish, and her father's face wore a look of quiet approval. On the whole, there was change enough to cause Flora to determine she would follow out the suggestion of her friend Ruth, and endeavor to make her home what she desired it to be.

When supper was over, Harry and Alec took their hats and went out, no one asking where they were going, or when they would return.

"How queer," thought Flora, who had volunteered to clear the table and wash the dishes, "how queer, that neither mother nor father seems to care where the boys[34] go, or what they do." And realizing the indifference of her parents, Flora began to feel an interest in the pursuits of her brothers.

When Flora retired to rest that night, she felt quite pleased with her experience of the afternoon and evening, and she intended that this should be the beginning of a new departure in her life; and she felt glad that she had found such a friend as Ruth. She arose early the next morning, and was downstairs before her mother was stirring. It was Sunday, and the entire family were in the habit of rising later than usual on that day.

"What a dingy old place this is, to be sure," said Flora. "I'll make the fire and straighten things up a little."

When she had finished she looked about, and shook her head.

"It doesn't look a bit comfortable, or homelike. No wonder the boys go out every evening. I do wish I knew where to begin to improve things, but I don't, and I have no one to ask about it, except Ruth; yes, I will talk to her about things. Perhaps she can help me."

When Mrs. Hazeley came downstairs, to her surprise and unbounded delight she found the fire burning, the[35] kettle boiling, and the table daintily laid, ready for breakfast.

"Why, Flora! I did not know you were up," she said, looking around, well-pleased with the generally improved condition of the room.

"I do believe your aunt has made quite a housekeeper of you," she continued, a moment later, as she inwardly congratulated herself upon the circumstance which had sent her daughter home.

Flora flushed at this unexpected, and for her mother, somewhat unusual word of commendation, but made no reply, for the simple reason that she did not know what to say. In spite of this feeling of pleasure that her effort was appreciated, she could not help wishing herself back in her aunt's home,—not as it now stood, with Aunt Sarah at its head, but as it had been under Aunt Bertha's gentle control. The more she thought of it, the more intense became the longing to be there in the old, happy, care-free life at Brinton. But there was nothing to be gained by wishing: Aunt Bertha was dead; Aunt Sarah was there, and there to stay; and she was at home, and here to stay; so there was nothing to do but to make the best of things, and get as much comfort out of[36] life as she could. Then she thought of Ruth's life, and her brave effort to make a home for her father and Jem, and inwardly Flora determined to emulate her example. How well she succeeded the future will show.

BREAKFAST over, and the dishes cleared away, Flora looked about, wondering what else there was for her to do. Her father was reading a paper, and the boys had gone away. She went to the window where Lottie's potato stood in its jar. The sight of it carried her thoughts back so vividly to the old days, that she half resolved to look at it no more.

She felt dull and spiritless to-day; it was no wonder, for there was little to make her feel otherwise. At Aunt Bertha's, every one had been accustomed to attend church, and Flora remained to Sunday-school. She had been converted and received into the church about a year before her aunt's death. Her sudden sorrow, her hasty trip from Brinton, and her unfamiliar surroundings in her new home, caused her to feel as if she had been removed to a heathen land.

None of the Hazeley household attended church, and Flora knew of no place to which she could go, for all was[38] so new and strange to her, and being somewhat timid, she would not go alone.

Still standing at the window, and looking drearily out on the quiet street, she saw Ruth and little Jem passing, on their way to church. When they saw Flora they stopped, and she, glad to see a friendly face, hastened to open the door.

"Would you not like to come with us to church, this morning?" asked Ruth.

"Indeed I should," replied Flora. "I was just wondering what I was going to do with myself to day. Wait a minute; I will be ready in a very short time."

As good as her word, she was soon ready. "I am so glad that you stopped for me, Ruth," said she, as they walked along. "I know nothing about the churches here, and no one goes from our house."

"That is too bad," returned Ruth, sympathizingly.

Flora was indeed glad that she had come when, as they ascended the church steps, she heard the deep tones of the organ pealing out a welcome to all who entered. As they walked up the aisle, it seemed as if the sweet notes of the music twined around them, as though enfolding them in a loving embrace. A feeling of quiet content[39] filled the heart of the young girl, and for a time the realities were forgotten in the soothing sense of rest that stole over her. Nor did she attempt to arouse herself until the opening services were ended, and the minister arose to announce his text.

In clear, distinct tones he read: "Whatsoever thy hand findeth to do, do it with thy might." Twice he slowly read the words, until Flora thought he surely must have pressed them right into her brain, for she felt that they were indelibly imprinted on her memory. Whether the sermon was intended especially for young people, or not, she did not know, but she felt that it was peculiarly adapted to herself. I have no doubt that the older folks felt the same with regard to themselves. It was one of those texts and sermons that suit everybody.

"I wonder how many of my hearers can say truthfully that they have done with their might 'whatsoever' their hands found to do," said the minister, looking, as Flora thought, directly at her.

She dropped her eyes uneasily to the floor, and mentally admitted, "I, for one, have not, unless it was to grumble and fret with all my might. I have done that, but nothing else, at least since I came home."

[40] "I am sure you cannot say that your hand has found nothing to do. You can perhaps say that your hand has not found what you wished it to do; but that is not what the words of the text teach. It says 'whatsoever thy hand finds to do.' Then too, it is to be done 'with thy might'; not half-heartedly."

"Oh," commented Flora to herself, "why should he talk so straight at me? If he is not describing Flora Hazeley, I am mistaken."

"Did you ever notice," the minister continued, "that when you did a thing heartily, even though it was not the most agreeable occupation to you, it became more easy and pleasant to you?"

Flora thought of the little help she had voluntarily given her mother the previous evening, and again inwardly agreed with the speaker. The minister said a great many things that morning, some of which had never entered Flora's mind, and they made her very thoughtful; so thoughtful that she paid but little attention to the strains of the organ that accompanied her out of the church. She remembered he had spoken of many kinds of work the hands might find to do, and which were to be done faithfully and heartily. Perhaps it would be church[41] work; perhaps professional work; perhaps mechanical work; and perhaps house-work and home-work. The last two, he thought, ought to go together, as neither could do very well without the other, although each differed in character. "House-work," he said, "as all knew, was sweeping, dusting, cooking, and the other duties connected with caring for the house; but home-work was the making and keeping a home; helping those in it to be contented and happy; brightening and making it cheery by both word and deed; shedding a healthful and inspiring influence, so that those around us may be the better for our presence."

"According to that, we all have a 'whatsoever,'" said Flora, emphatically to herself; "and the sooner I decide to start on my own part, the better it will be for me."

With her mind busy with many things, Flora was very quiet on her way home. The sermon to which they had listened was plain and practical. It was not brilliant, but it was helpful. The ideas were not necessarily new, but the words fell upon at least one heart already prepared and softened by circumstances to receive and profit by them. To Flora they were seed, falling upon the prepared ground of her heart, and in due time the fruit came[42] forth. Most of the suggestions were new to her, for never before had she viewed them in this particular light.

Ruth respected her friend's silence, for she saw that she was busy with her thoughts, and guessing something of what they were, she was also quiet. Jem was unaffected by the silence of her elders. She walked along at Ruth's side, with her hand closely holding her sister's. Her happy life caused her every now and then to lapse from her dignified walk, and give a little jump and a skip. A continual volley of questions was thrown at Ruth, whose replies were not always as obvious as occasion demanded.

Jem's quick retort, "No, it isn't, Ruth," brought her to a realization of her abstractedness, and she resolved to be more attentive.

They left Flora at her door, Ruth asking if she had enjoyed the service, and added:

"Will you not come to Sunday-school with us this afternoon?"

"I did enjoy the sermon very much," Flora replied, "and I shall be pleased to go to Sunday-school. If you will call for me, Ruth, I will be ready when you come."

A number of things grew out of Flora's experience on this Sunday. Its influence stayed with her, and had no[43] small part in shaping her future life. She soon became an earnest worker to make the world better for her living in it; striving patiently and faithfully to render her daily life a power for good to those around her. How she succeeded our story will tell. Last, but not least, a strong affection sprang up between Ruth and herself, which proved a blessing to both.

Ruth taught a class in the Sunday-school, and persuaded Flora to consent to take one also, if the necessity arose. She introduced her to the superintendent, who welcomed her cordially to the little band of Christian toilers.

"One class is in need of a teacher," he said; "will you not take it? It is composed of girls from ten to twelve years of age."

"Oh, I should not dare to undertake a class of girls so old!" exclaimed Flora. "I am too young myself. Give me little girls, such as Ruth has."

"But," said Mr. Gardiner, "there is no such class in need of a teacher. Besides, it is not the age that has to do with your success as a teacher; it is the earnestness, perseverance, patience, and true piety which you bring to the work that will bring forth the results you desire."

"I am so inexperienced," murmured Flora.

[44] "Neither has that anything to do with the matter," contended the gentleman, smiling. "Experience will come, all in good time," he added.

"Well," said Flora, "I will do my best."

"That is right," answered Mr. Gardiner, heartily. He felt sure that the young girl before him would succeed, for energy, conscientiousness, and determination could be read plainly in her bearing, and these, he knew, were characteristics of a successful teacher. He was glad, therefore, he had persuaded her.

Ruth, also, was pleased, for now her friend would be also a co-worker.

Flora felt sad when she thought that her family were the only ones of those who knew her who were entirely indifferent as to what she did or where she went.

"Only think, Ruth," she said to her friend, "it doesn't matter to them, whether I go wrong or right. What encouragement is there for a girl in my place to try to do right?"

"It does seem hard, dear," the gentle friend replied; "but then you will shine out all the brighter in the end for doing right in the face of discouragements; and God cares, you know."

[45] They were at the gate, and bidding Ruth good-bye, Flora slowly went up the path to the house, her brain very active with new thoughts and purposes.

"Yes, God will help me, if I ask him," said Flora, softly, as she went to her room, and after doffing her hat and jacket, she knelt beside her bed, and asked the dear Lord to bless and strengthen her in her new surroundings, and let her life tell for him.

MONDAY morning was cloudy. Flora felt gloomy and dispirited, and notwithstanding her good resolutions, not in a mood to make any extra exertion.

Mr. Hazeley had gone to his work, Harry and Alec to school, and the mother was in bed with a sick headache. Flora was lonely. There was much to be done, she realized, but just where to begin she did not know. There was no one to tell her what to do, and everything looked very dark to her on this Monday morning.

The dishes were nicely washed, and carefully put away. The little dining room had been swept and dusted, and looked somewhat more inviting. The window where the sweet potato, the last link binding her with the past at Brinton, stood, had been washed until the glass fairly shone, and now she stood gazing listlessly out into the street.

Presently she saw Ruth, on her way home from market. When in front of the house, Ruth looked up, and saw[47] Flora's woe-begone face at the window. She stopped, and gave her a smiling little nod. Flora's countenance brightened immediately, and she hastened to meet her.

"You look lonely, this morning," was Ruth's greeting.

"Indeed, I feel so," admitted Flora.

"If you are not busy come home with me for a while."

"I should like nothing better," cried Flora. "Just wait until I tell mother."

In a moment she was back, and the two walked on, Flora insisting on helping Ruth with her market-basket.

Jem met them at the door of the tiny house, and conducted them in with great dignity. Flora was delighted with everything.

"What a dear little house," she exclaimed, glancing about her admiringly.

"I am glad you like it," said Ruth, looking pleased.

"And what a dear, little, old-fashioned housekeeper you make!"

"Do you really think so?"

"Of course I do," said Flora, heartily. "Ruth, dear," she continued, abruptly changing the subject, "I want a talk with you."

"I shall be so glad to have you," said Ruth, seating[48] herself, with a pan of apples in her lap. "Sit down beside me, and you can talk while I pare these apples."

"I will help," replied Flora. "Run, Jem dear, and get another knife for me, like a good girl."

Jem obeyed, and soon returning, brought with her a box filled with bits of calicoes, and various odds and ends, seated herself also, and proceeded to fashion what she was pleased to call "doll's clothes."

"Ruth," began Flora, after they were all settled and busy, "I like you ever so much, and I hope we always will be friends. You seem to know so much, and you have had so much experience, that I am sure you can help me a great deal, if you will."

"Of course, dear," was her gentle reply, "I would be glad to help you all I can, and I shall be as pleased as possible for us to be friends. As to my knowing much, you are mistaken; I know but very little of anything; and experience,—well, I have had some, I suppose; but then, it isn't the sort that would help you, I am afraid. However, I shall be glad to do anything I can for you."

"I am sure you can help me, Ruth. You have helped me already," said Flora, decidedly. "And I mean to do as you suggested, and try to make my home just what I[49] would like to have it. I don't know how to begin exactly; and then, mother never seems to care how things go, and that makes me feel as if I did not care either."

"I don't like to hear you talk about your mother so, Flora dear," said Roth, in a troubled tone.

"How are you to help me, if I don't tell you just what I think and feel?"

"Perhaps, if you were to let your mother see and know that you wanted to help her, and make things bright, and talk with her——"

"Talk!" interrupted Flora; "I don't believe she would do it, even if I were to try."

"Oh, but have you tried yet?" asked Ruth, looking up archly. "You cannot tell until you do."

"Very well," said Flora, laughing, "I guess I shall try. But there is another thing," and the troubled look returned to her face. "It is about the boys, my brothers. They stay at home scarcely ever. I don't know where they go so often, and I am sure mother does not, and I don't believe she cares—you need not look grave again, Ruth—I don't. Harry and Alec seem to be good boys, and it is a pity they are not restrained. They may get into bad company—if they are not in it already—and do[50] something dreadful, and bring disgrace on us all. What can I do about that?"

"It would take a wiser head than mine to tell you that," Ruth answered; "but you might try and see if you could not make it so pleasant at home they would not care to be away so much."

"It seems pretty plain to me that that is easier to say than to do," retorted Flora, just a little impatiently.

"Yes, I know," assented Ruth, meekly; "I don't pretend to be a Solomon; I only said you might try."

"I don't believe they would stay for me," contended Flora, stubbornly.

"That is another thing you have never tried yet," said Ruth, smiling mischievously.

"That is so," laughed Flora, as she took two or three curly parings, and put them on Ruth's hair, to show penitence for her contrariety. "I guess I had better not talk any more, until I have tried to do something. I don't know how to begin my reformatory measures, but I suppose all will be well if I start with 'whatsoever.'"

By this time the apples were finished, and she rose to go.

"You haven't remired my doll's things," said Jem, reproachfully.

[51] "So I have not," said Flora, and she sat down beside the little seamstress, and began to "remire" the various articles held up for inspection. She was compelled to see through Jem's eyes, however, for the shapes of the garments were not so striking or familiar as to suggest their names.

When at length she reluctantly took her leave, Ruth invited her to come soon again, to which she laughingly replied she certainly should. After this, matters went on more pleasantly at Flora's home. She busied herself with making the house look as cosy and as attractive as the shabby furniture and worn carpet would admit. She succeeded beyond her own expectations. She was gratified also that her brothers seemed to enjoy the improved condition of affairs, and so did her father when he was at home. Lottie's potato was now adding its mite to the general reform, and was sprouting nicely, sending its delicate white roots downward into the clear water, and its closely folded leaflets upward, to grow green in the warm sunlight. It seemed to be quite at home in the bright window. Flora had ceased to dream when she looked at her quaint friend. The days now, were too full to build air-castles. Mrs. Hazeley was pleased to shift her responsibility[52] to Flora, who enjoyed nothing better than to have all her time occupied. Often, when tangles would come, Flora would run over to the ever-sympathetic Ruth, and receive advice from her. Thus, in being busy, Flora became more content, and often, as she thought of Aunt Sarah, she knew she would not be found fretting.

She had not yet attempted to influence the boys by word, but they soon noticed the new air of homeliness pervading the rooms, and consequently did not go out so much as had been their custom. Alec, the younger boy, was very mercurial and mischievous, while Harry, the elder, was quiet, and fond of reading.

One evening Harry seemed to be more than usually inclined to be sociable, and gave his mother and sister an animated account of something that had happened "down town," that day. When he finished he took up his book, and was just preparing to read, when Flora, eyeing the volume distrustfully, asked:

"What are you reading, Harry?"

Harry looked up at her quizzically, and answered her question by another.

"Why? What is it to you, anyway?"

"Nothing," said Flora, rather disconcerted. She was[53] unaccustomed to boys, and had but little tact in dealing with them.

"I thought so," replied Harry, coolly, returning to his book.

"Will you not tell me what you are reading?" again asked Flora, not willing to be so easily vanquished.

"Why do you want to know?" demanded Harry, looking at her suspiciously.

Flora's lips again framed "nothing," but no sound came, for like a flash she thought, "If I say that, he will say, 'I thought so,' as he did before. No, I will give a reason," so she said:

"You seemed to be so interested in it, I thought it must be very entertaining."

"So it is," replied Harry, throwing a mischievous glance over to the corner at Alec, where he sat thoroughly engrossed in his favorite pastime of whittling, and in serene thoughtlessness allowing the clippings to fall according to their own sweet will.

Harry was confident that Flora intended to "read him a lecture upon trashy literature," as he afterward privately told Alec. He replied:

"It is interesting, Flo, about murders, and bears, cut-throats[54] and burglars, and other horrors that would make you nervous to read about."

"I am not made nervous so easily as you may think, my dear boy," retorted Flora, condescendingly, and at the same time glancing cautiously at Harry, to see what effect this would have.

She had determined to try and gain an influence over her brothers, and felt that to show an interest in their occupations would be a good beginning. She realized the task she thus imposed on herself, but she meant to do her best, for this was another "whatsoever."

Harry was for a moment too much surprised to speak. Then he said, saucily:

"Ah, indeed! Well, let me read some to you."

"I shall be glad for you to read to me, if you will read a story I have just started. I feel sure you will enjoy it. If yours is a book for boys only, I fear I could not appreciate it."

"Oh, you couldn't?" said Harry. "Why not, may I ask?"

But Flora was up and away ere the sentence was completed. Harry congratulated himself on having put her to flight, and returned to his book with a self-satisfied[55] smile. Flora, however, had only gone to her room for a paper. Hurrying back, she spread it before astonished Harry, and, pointing to its columns, said, in a peculiarly persuasive manner:

"Now, Hal, I would be ever so glad if you would read that story aloud to us, while I crochet, and Alec whittles on the floor."

Alec looked confused, and began to pick up some of the litter he had made.

"Never mind, Alec," said Flora, laughing, "I will clear it up this time. Could you not put a newspaper under you to catch the cuttings, another time?"

"All right," said Alec, looking relieved.

"We are all ready, Harry," said Flora, sitting down and taking up her work.

"Humph!" said Harry, glancing carelessly down the page. "There's nothing in such a story. I don't want to read it. It is too flat."

"You are mistaken," replied Flora, spiritedly. "It's not a bit flat, and there is something in it. It is about a brave boy who saved a train."

"Oh, yes, I know," said Harry, skeptically, "and was not hurt."

[56] "Yes, but he did get hurt. Why not read it, and see?" suggested Flora.

"Yes, read it, Hal," said Alec; "let's see what it is, anyway."

"All right," and Harry began to read with a comical nasal twang, very rasping to Flora's feelings, but she had the wisdom to say nothing. She was very glad, later, because Harry gradually dropped the false tone, and she could see by his manner that he had become interested, in spite of himself. Alec too, had ceased whittling, and was listening intently.

Forgetting to criticise, Harry read the entire story, which, in truth, was a pathetic little incident, very gracefully and entertainingly told. He was silent, as he laid the paper on the table, but his thoughts were busy.

"I was right, was I not, Harry?" asked Flora.

"Yes," drawled Harry, smilingly, "you were. I did enjoy it, and I am glad you asked me to read it. But, let me see," he added, turning to the clock, "what time is it? Well," and he laughed, "I was good. It is nearly ten. Guess I will retire; I was going out, but it is too late."

Flora was secretly rejoiced to hear this, but she simply[57] said, "Good-night." She felt a glow of satisfaction as she realized a beginning had been made toward gaining the hold upon her brothers she so much desired.

"Flora, will you lend me that paper?" asked Alec, as she was preparing to go to her room. Flora willingly placed the paper in his hand, remarking, as she did so,

"I am glad you like the story. I have others, if you want them. Aunt Bertha kept me well supplied."

"Good night," returned Alec, and he was gone.

Flora was more nearly content than she had been for some time, as she sank into peaceful slumber that night.

I BELIEVE I am going to realize some of the dreams I used to have, after all," Flora said to herself, as she laid her head upon her pillow that night.

She was right. The first step had been taken by her in the path of becoming an earnest worker, and to influence those about her as she had planned she would like to do, although not in such a way as this, nor in such surroundings. Her cherished dream of being instrumental in leading others into a higher and better life was now, she began to realize, leading her into the lines of duty in her own home, and among her own people. She could not wish for more.

She would not be like so many others, who in their desire to do great things, neglect the opportunities near at hand, and who, in longing to lead the heathen to a higher plane of life, forget those at home, who possibly for want of a word or act, have slipped, stumbled, and fallen on life's pathway.

[59] Flora was growing, and with an earnest prayer to the Christ for guidance, strength, and tact, she cheerfully assumed more duties in the home, and greater responsibility. Her bright, sunny disposition, her pleasant face, her extreme willingness to respond to requests, gradually won a place for her in the hearts of those in her home.

The class in Sunday-school was assumed with a feeling of great apprehension. It was composed of five girls between the ages of ten and twelve. At first sight of their youthful teacher, these girls had been inclined to be displeased, but when they grew to know the sunny, sweet good-nature, born of the great desire to do them good, and which shone out of the earnest eyes, they loved her dearly. The teaching of this class was fraught with great good, both to the teacher and scholars, and this meeting with the eager, bright girls was soon eagerly looked forward to by Flora from week to week.

"How things have improved at Mr. Hazeley's!" soon grew to be a common remark among the neighbors.

"Yes, since Flora came home, it has become very different from what it formerly was," would be the spirit, if not the words of the reply.

Flora overheard a similar remark one day, and it gave[60] her a feeling of great joy to know the change was becoming apparent. Her resolution was strengthened to sustain this newly made reputation.

It must not be supposed that she always had an easy time. This was not so, for as she often said to Ruth, "When mother and Harry are not in a good humor, things do become tangled."

However, to do the family justice, they were beginning to see and to more fully appreciate the changes made in their home since Flora, who had left them a small maiden, had returned with her thoughtful ways and mature manner. They forgot sometimes that she was but sixteen, and would fancy she was older than she really was. In fact, almost imperceptibly, she assumed all responsibility, and they deferred to her judgment in many things. Best of all, however, they began to love her.

Her younger brother Alec seemed to have entirely surrendered to her gentle, loving rule, and was ever willing to listen to her advice. He was always ready to help her by running errands, chopping wood, drawing water, and performing a dozen other little tasks quite new to him, for he had never aided his mother in any way. In fact she had never asked her boys to assist her,[61] or to save her extra steps or work, forgetting it ought to be required from them.

Mrs. Hazeley also had changed under the magic wand of Flora's sunny influence and determination to win the love of all. She had become at least a willing agent to the general change taking place in her home, and which recommended itself to her because her responsibilities were lightened and carried by other shoulders.

The house itself was transformed. Even cynical little Jem was becoming satisfied with it. It still contained the same furniture, but there was an air of comfort and home life about it never there before, but introduced by the magic of Flora's presence.

Lottie's sweet potato added its share to the general improvement which was going on. The long thread-like roots looked very white in the jar of water in which they were growing, and the graceful tendrils and light-green leaves were quite refreshing to the eyes. Flora had trained the vine about the window on small cords, and already it had nearly covered the lower part with its delicate branches. Flora would have felt lonely without it to care for; especially after being accustomed to have plants in profusion around her at her old home. Then[62] too, it carried her back to the happy days at Aunt Bertha's, bringing a feeling of joy that she had been permitted to live there so long, and to be trained in such a gentle, firm, loving manner. Frequently she mentally contrasted her care-free life there, and her life of responsibility now, and she determined, with the help that is from above, she would not sink to her surroundings, but would elevate them to her level. Bravely, patiently, hopefully did she go forward with this end in view.

She was really surprised to find how fond she had grown of her brothers, and they of her. She could think of her mother very differently now, and she in turn began to show signs of an awakening affection for her daughter.

As to Ruth, she was ever the same, a quiet little home body, whose hands were always too full to allow her to come to Flora, but whose demure little face never failed to smile a welcome to her friend, and whose wise brain could turn over Flora's tangles and straighten them.

The two girls loved each other dearly; and no safer, truer friend and guide could Flora have found than Ruth Rudd, who, although no older than she herself,[63] was very mature in thought, manner, and speech. Her face however, was childlike and innocent, reflecting the pure soul within. Flora was fortunate indeed in having her for a friend and confidante.

Harry Hazeley was a manly fellow with fine qualities. He had been allowed to do as he pleased, and had not been greatly benefited by this freedom. No restraining hand or guiding voice had been held out to him, or to cheer him on his way. Not being evil minded, he had taken but few wrong steps, and now his attention had been attracted to higher and better things.

As I have said, Harry had good qualities; one of which was a kind disposition, and although it was not always apparent to his every-day associates, was brought into play whenever he met any one who seemed in need of assistance.

One morning, as he was walking through the market on his way to school, his attention was attracted by an old man. One of his feet was swathed in bandages, and he was hobbling painfully back and forth, from his wagon to the stall, where he was trying to arrange a quantity of vegetables and some flowering plants which formed his stock in trade.

[64] Harry had a quarter of an hour to spare, and he immediately offered to help the old man, who was only too glad to accept the proffered assistance, and who introduced himself, between the journeys from stall to wagon, as "Major Joe Benson, a gardener on a small scale."

Major Joe was an old ex-soldier, who had been wounded, and later imprisoned. The title "Major" was only a nominal one, and not indicative of any rank. His name, as he informed Harry, was Joseph Major Benson, Major being his mother's maiden name. He preferred to transpose this and call himself Major Joseph Benson, shortened for convenience to "Major Joe."

"It sounded sort of big, you know," he said, drawing himself up and looking dignified, until reminded by a sharp twinge in his foot that "rheumatiz" and dignity did not agree.

Major Joe was very talkative, and would not cease his persuasions until Harry had promised to drive out to his home with him some day, and see his nice little farm and Mrs. Benson, and he added:

"She will be delighted to see you, because you possess such a kind heart, and because you helped me. You must come."

[65] "Yes, I will," returned Harry, "but I must be off to school now. Good-bye." And away he went, mentally pronouncing the major "a jolly old chap."

The visit was made, and strange though it seemed, a fast friendship sprang up between the two, and the visits became quite frequent. Harry had taken Alec with him several times, and he too had greatly enjoyed the trip. Major Joe could tell any number of quaint tales and reminiscences of interest to the brothers. Mrs. Benson, who was more active than her husband, was always desirous for Harry and Alec to remain to tea. Her heart had been reached by the kindness of Harry to her "Major," as she lovingly called him, and she could not do enough for them.

Harry had passed his old friend's stall a number of times since Flora's return, and had of course told him about his sister. The major had a strong desire to see this wonderful girl, as he deemed her to be, from the glowing descriptions that came to him. Finally he insisted, and Mrs. Benson sent in a kind invitation that the three, Harry, Flora, and Alec must come home with him to spend the afternoon and take tea.

He chose a beautiful day in early summer for the[66] visit, and Flora was anticipating it with no small degree of pleasure, for it would be the first real holiday she had had since coming home. The thought that the boys cared enough about her to plan a trip for her was a very pleasant one. Her mother seemed as much pleased with the idea as the rest, and had insisted upon her going, so Flora felt warranted in thoroughly enjoying her new experience. Mrs. Hazeley was daily becoming more energetic, and seemed really arousing to the fact that she had a place to fill in her home.

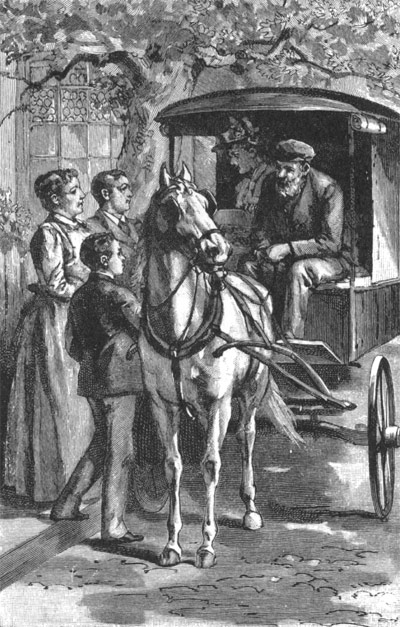

Major Joe was to call for his three young friends on his way home from market. He had promised to be on hand by noon, and as punctuality was an economizer of time, in the old gentleman's opinion, it was barely twelve o'clock when he drew up with a great attempt at flourishing before the Hazeleys' door.

Hazeley Family.

Hazeley Family.QUITE an effort was necessary in order to arrange the board for an extra seat for Flora and Alec. At length it was made ready, and Flora was helped in, and Alec followed, while Harry took his place beside the major, who commented as follows:

"So this is your sister, Harry? Well, well, she's a sister to be proud of; and I haven't a doubt but you are proud of her. Here, you Jacob, git up, will you?" and he shook the reins vigorously over his horse's back. "You never do come to a standstill but what you think it's meant for you to go to sleep."

Jacob, roused from his intended doze, lazily shook his fat sides, and slowly moved along. It was a lovely June day, and the little party had a very pleasant ride of about an hour and a half, Jacob not being inclined to hurry.

Major Joe was conversationally inclined, and nothing pleased him more than to hear the sound of his own voice. He chatted continually: now about the orchards they[68] passed, and their probable yield of fruit; now about the styles of the houses, as they came into view, and interspersed these remarks with reminiscences of the time when he was in the army.

The ride seemed quite a short one to Flora, who had enjoyed it thoroughly.

Mrs. Benson stood at the gate, watching for them; and in her white kerchief and neat cap, looked good-natured and comfortable. A saucy little spaniel sat in the middle of the road, watching too; and he was the first to catch sight of the wagon. He gave notice of the same by a sharp bark, and springing to his feet, doubled himself together, and bounded away, raising a cloud of dust in his haste to reach and greet his master. How happy he was when he reached the carriage! He sprang up at old Jacob, who paid no attention to such a small animal, but merely turned away his head with an air of supreme indifference.

"Jump, Dolby, jump!" said Major Joe. After several ineffectual trials, and two or three hard falls into the dusty road, Dolby landed beside his owner, who had made room for him, and gave himself a vigorous shake, which sent the dust he had gathered in his long hair, over[69] Flora's clothes and into her face, causing her to choke, and a moment later to laugh. Dolby concluded this was in recognition of himself, and turning around, eyed Flora quizzically, and gave a satisfied little friendly bark.

The garden and nursery belonging to Major Joe were not large, but they were very fruitful, enabling him to realize considerable from the sale of his flowers and vegetables. He did not carry on his trade in a scientific manner, but merely for his love of the beautiful and useful things of the vegetable kingdom, and because to be inactive was for him to be unhappy. His receipts from the sale of the products of his land, together with his pension, enabled himself and Mrs. Benson to live very comfortably in their own snug little cottage, and, in addition, to lay aside something for a rainy day.

"Well, mother, here we are," said Major Joe, throwing the reins over Jacob's back.

"So I see," answered Mrs. Benson, nodding smilingly to the entire party. "Just come right in," she added, as Alec sprang out on one side of the wagon, and Harry helped Flora from the other.

The young people followed their hostess through the gate, and up the box-bordered walk into the cosy little[70] cottage. Flora was soon seated in a low rocking-chair by the window, whose broad sill was filled with potted plants.

There Harry and Alec left her in good Mrs. Benson's care, while they went for a walk over the place.

Flora soon discovered that her hostess was as sociable as the major, and but a short time passed before they were chatting like old friends.

By-and-by, Alec thrust his merry face in at the door, and said:

"Come out here, Flora; the major wants you to see his garden."

"Yes, dear, go, if you are perfectly rested," said Mrs. Benson. "I will stay here, and see about preparing our early tea."

Flora joined her brother out of doors, and found Major Joe and Harry waiting.

"Come and see my little green-house," said the old man, waving his hand, and looking at them from over his spectacles with an important air. Flora complied quite willingly, for she was very fond of flowers, and immediately won the major's good opinion with her enthusiasm over his pet plants, and the interest with which she[71] listened while he enlarged upon his management of them. The care of his garden was a tax upon his time, and really constituted quite a little labor. Then, outside, it was so pleasant to walk up and down among the neat flower-beds, in the small, but nicely kept orchard; and in the kitchen garden, for the major prided himself on his choice vegetables, some of which frequently took prizes at the county fair.

The major himself was in his glory, for he had someone to whom he could talk. Talking was an occupation of which he never wearied, and now he chatted about the various departments of his labors, and how pleasant it was to watch the growth and development of the plants.

His tongue was still going very fast, when Mrs. Benson appeared in the doorway, and called to them that tea was ready. Reluctantly the old gardener relinquished his young listeners, who were, however, quite willing to vary the program, for they were hungry. The sight of the pleasant room, neat tea-table, and their genial, motherly hostess, was a very inviting one. In a lull of the conversation, during the progress of the meal, Mrs. Benson remarked, with a sad little smile, that Flora reminded her of her Ruth.

[72] "So she does," exclaimed her husband. "I knew she made me think of somebody, but couldn't make it clear who it was."

"Is Ruth your daughter?" asked Flora.

"She is, or leastways she was," said Mrs. Benson, heaving a sigh, and adding, in a low voice, "She's dead now."

"I am very sorry," said Flora, with ready sympathy.

"Yes, our Ruth was a fine girl, but a little headstrong. We did all we could to make her happy and contented at home, but it seemed as if we did not succeed, and so, one day she ran off to marry a man we couldn't care for, because we were sure he wouldn't treat our girl kind—not that there was anything against him, but he was so cold and unfeeling. But she wouldn't listen to us, and went off, and we never saw her again."

"How sad!" said Flora; "but couldn't you go to see her?"

Mrs. Benson shook her head. "No; he said we were not to have anything to do with Ruthie, after he married her, and they moved away somewhere, we never knew where, until we heard in a roundabout way that she was dead." Here Mrs. Benson paused to wipe away a tear. "I had hoped she would at least have stayed near home,[73] and been a comfort to us in our old age; but, I suppose it's all right, and for the best. But excuse me for telling you so soon of our great sorrow. I should not have done it. Have you ever heard," she continued—and soon all were laughing heartily at her quaint sayings.

Flora, however, could not send from her thoughts this sad story. When the pleasant visit was drawing to an end, and they all were bidding Mrs. Benson good-bye, promising to come again, it still lingered with her. As old Jacob was soberly and deliberately trotting homeward, she revolved it over and over in her mind. Somehow it fastened itself upon her in a way she did not understand, and not until she was home, and had retired to her room for the night, did she arrive at even a partial solution of the perplexing problem. Then it dawned upon her with surprising clearness, that it certainly was because of the similarity of names in Mrs. Benson's daughter and her friend and adviser, Ruth Rudd.

This was very slight ground on which even to build an air-castle, but Flora did not stop to consider that, but in the midst of her dreaming resolved to go the next day, and rehearse to Ruth the story she had heard from Mrs. Benson.

[74] Accordingly, next morning, after the work was done, and her mother was seated with her sewing, Flora donned her hat, and went to see her friend, expecting to find her busy as usual. She was, therefore, very much surprised to be met at the door, even before she had knocked, by Ruth herself, whose gentle face wore a troubled, anxious look, and she spoke in a low tone, as she responded to Flora's query:

"What is it, Ruthie?"

"Father is very sick."

"Oh, I am so sorry! What is the matter? When was he taken ill? Was it suddenly?"

"Yes and no," said Ruth, answering simply the last question put by Flora. "He was compelled to stop work yesterday, and come home. He has been in poor health for a long time. I have been afraid, for quite a while, that he would break down."

"The doctor does not think he will die, does he?" whispered Flora, in an awed tone.

"Yes, he does," said Ruth, as she wiped her eyes with the corner of her apron.

The two girls, with their arms entwined, and a deep tenderness in their voices, then went into the little[75] kitchen, where Jem sat, holding her beloved kitten close to her for comfort.

"Yes, the doctor says that he cannot last long. But what bothers me is, there seems to be something on his mind, and I can see he is worried."

"What about? Do you know?" asked Flora, sympathizingly.

"Well, I can guess," Ruth answered, taking from a work-basket a stocking of Jem's, and beginning to darn it in an abstracted, mechanical way.

"You see," she continued, "father married my mother—my own mother, I mean—against her parents' wishes—she was young—and he never would be reconciled to them, because they had objected to him. Neither would he allow them to have anything to do with each other afterward. He was very stern, and it all made mother so unhappy it just broke her heart, I am sure. She died when I was very small. He has told me, since Jem's mamma died, he wished he had tried to pacify my grandparents. But he had moved far away from them, and now, if he should die, he has nobody with whom to leave Jem and me. But he was always so proud; and now we shall be all alone," and she gave a sorrowful little sigh.

[76] "See here, Ruth," exclaimed Flora, a sudden thought flashing across her mind. "What was your mother's name?"

"Ruth, it was the same as mine," was the reply.

"Yes, but what was her last name?"

"Benson, I think."

"Well, then, I think I know your grandparents," cried Flora.

"You do? How? Where?" returned Ruth, in a puzzled, disjointed way.

"Wasn't, or isn't, your grandfather named Joseph Benson?" asked Flora.

"Yes, Joseph Major Benson; but how did you know?"

"Oh, I found out," was the answer. "And they live just a little way out in the country."

"But, how do you know all that?" persisted Ruth, incredulously.

"Because I was there yesterday."

"Oh, Flora, are you sure? Don't raise my hopes and then disappoint me."

"My dear, you will not be disappointed; I should not like to do that," said Flora, gravely; "but let me tell you, and you can see for yourself." And then she told the story[77] Mrs. Benson had told her, ending with, "So, you see, there can be no mistake."

Ruth was delighted, and thanked her friend again and again.