Project Gutenberg's The Boy Scouts Down in Dixie, by Herbert Carter

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The Boy Scouts Down in Dixie

or, The Strange Secret of Alligator Swamp

Author: Herbert Carter

Release Date: February 13, 2015 [EBook #48251]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE BOY SCOUTS DOWN IN DIXIE ***

Produced by Stephen Hutcheson, Rod Crawford, Rick Morris

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

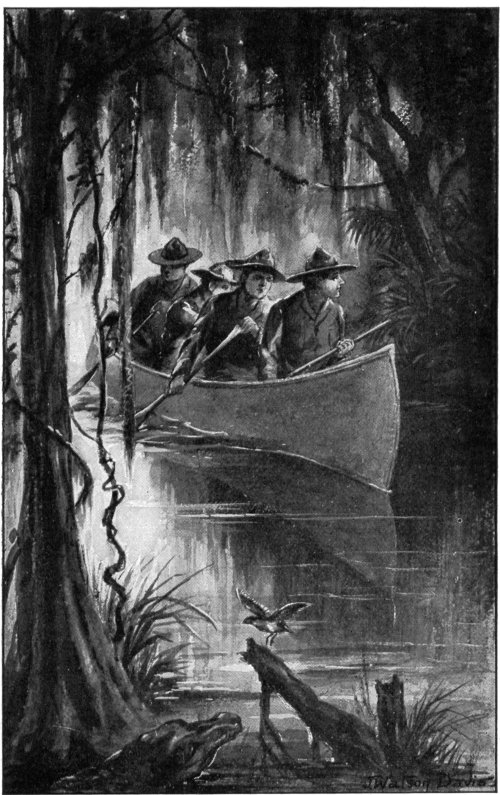

“Back water, fellows,” called out Step Hen;—“What’s up?” asked Giraffe. Page 119. —The Boy Scouts Down in Dixie.

OR

The Strange Secret of Alligator Swamp.

By HERBERT CARTER

Author of

“The Boy Scouts at the Battle of Saratoga.”

“The Boy Scouts Through the Big Timber.”

“The Boy Scouts On Sturgeon Island.”

“The Boy Scouts In the Blue Ridge.”

“The Boy Scouts’ First Camp Fire.”

“The Boy Scouts In the Rockies.”

“The Boy Scouts On the Trail.”

Copyright, 1914

By A. L. Burt Company.

“That’s always the way it goes!”

“Why, what’s the matter with you now, Step Hen; you seem in a peck of trouble?”

“Who wouldn’t be, when some fellow went and hid his hat away? Didn’t you all see me hang the same on this peg sticking out from the trunk of the pine tree, when we-all came ashore to eat lunch; because that’s what I did, as sure as anything?”

“Oh! you think so, do you?”

“I know it as well as I know my name. Think because I’ve got a stuffy cold in my head just like Bumpus here says he has, and can’t smell, that I don’t know beans, do you? Well, you can see for yourself, Davy Jones, my nice new campaign hat ain’t on the peg right now.”

“Do you know why that’s true, Step Hen? Because a thing never yet was known to be in two places at the same time. And unless my eyes are telling me what ain’t so, you’ve got your hat on right at this minute, pushed back on your head! Told you, boys, Step Hen ought to get a pair of specs; now I’m dead sure of it.”

The boy who seemed to answer to the queer name of Step Hen threw up a hand, and on discovering that he did have his hat perched away back on his bushy head of hair, made out to be quite indignant.

“Now, that’s the way you play tricks on travelers, is it? I’d just like to know who put that hat on my head so sly like! Mr. Scout-master, I wish you’d tell the fellows who love to play pranks to let me alone.”

“I’d be glad to, Step Hen, only in this case I happened to see you take your hat down, and clap it on your own head, though I reckon you did it without thinking what you were doing; so the sooner you forget it the better.”

A general laugh arose at this, and Step Hen, subsiding, continued to munch away at the sandwich he gripped in one hand. There were just eight lads, dressed in the khaki suits of Boy Scouts, some of which were new, and others rather seedy, as though they had seen many a campaign. But those who wore the brightest uniforms did so because their others had become almost disreputable, and fit only to be carried along for use in case of absolute necessity.

While they sit there, enjoying their midday meal, with two pretty good-sized paddling boats tied up, showing just how they managed to reach this lonely place on the border of one of the almost impenetrable swamps in Southern Louisiana, let us take advantage of the stop to say a few words concerning these lively lads.

Of course the boy reader who has had the pleasure of possessing any or all of the previous volumes in this series, will readily recognize these sturdy fellows as the full membership of the Silver Fox Patrol connected with Cranford Troop of Boy Scouts.

Under the leadership of Assistant Scout-master Thad Brewster they had been having some pretty lively outings for the last two years; at one time in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina; then up in Maine; afterwards finding a chance to pay a hunting and exploring trip to the far distant Rocky Mountains, and finally on the preceding summer cruising upon the vast stretches of Lake Superior.

Besides the patrol leader, Thad, there were Allan Hollister, who had seen much actual life in the woods, and was perfectly at home there; a tall lanky fellow, with such a long neck that his chums had long ago named him “Giraffe;” a dumpy, fat scout, whose jolly red face was almost the color of his hair, and who came when any one called “Bumpus;” a very neat and handsome boy who had been christened Edmund Maurice Travers Smith, but who did not object when all that was shortened to just plain, every-day “Smithy;” an acrobatic chap who loved to stand on his head, and play monkey, Davy Jones by name; Step Hen himself, otherwise Stephen Bingham; and last but not least one Robert Quail White, a native of the South, and whose rather odd name was soon happily changed among his mates to plain “Bob White,” which, as all boys know, is the popular way a quail is designated in the country.

It might as well be said right here in the start that Bumpus was also occasionally at school and at home addressed as Cornelius Hawtree; and that Giraffe would come to a meal if some one called softly “Conrad Stedman;” because he was very, very fond of responding to any sort of a summons that had something to eat along with it.

These eight boys did not constitute the whole of Cranford Troop, for there was another full patrol enlisted, and part of a third; but they were all boon companions; and chancing to have a snug amount of hard cash in the treasury of the patrol, separate from the troop amount, they were enabled to take advantage of a golden opportunity to visit the far South in the dead of winter.

It chanced that they were talking about this right then and there, so that by listening for a bit we may learn what unusual circumstances had arisen to give the scouts this wonderful chance to take a vacation, when they apparently should be industriously working at their books in the Cranford High School, to which all of them belonged.

“You can say what you like,” Giraffe was remarking, as he carefully drained the coffee-pot into his tin cup, that being his third allowance; “I think the Silver Fox Patrol was hatched out under a lucky star. We’ve had heaps and heaps of good things happen to us in times past; and now just to think that the old frame building we’ve been using for a high school for years, should go and take fire and burn to the ground, a month or six weeks before the new brick schoolhouse could be furnished and heated, compelling the Board to dismiss school for that time. Let me tell you it’s a mighty bad wind that blows good to nobody.”

“But that’s only a part of our great good luck, and you forget that, Giraffe,” insisted Davy Jones, nodding his head, eagerly, as he looked around at the live oak trees, in the crooked and wide spreading branches of which he expected to soon be sporting, holding on with his toes, and swinging from limb to limb with the abandon of an ape.

“Why, to be sure, I had ought to enumerate the rest!” declared the lanky member of the patrol. “Think of it, how just after that sad catastrophe—excuse me, boys, while I wipe a tear away in memory of that poor old schoolhouse—there was that strange letter came to Thad’s bully old guardian, Daddy Caleb Cushman Brewster, from a man he used to know years ago. It was written from down here in Southern Louisiana, and told how the writer had seen one Felix Jasper, with a very pretty if ragged little girl in his company, hurrying along a lonely trail that led into old Alligator Swamp, and acting like he had recognized the gentleman, and was afraid to let him come any closer.”

“Yes,” spoke up Thad, who in the absence of the regular scout-master, Dr. Philander Hobbs, always acted as the leader of the troop, “and all of you chance to know that years ago, when I was much smaller, and lived in another town, that man Felix Jasper was the manager of my mother’s estate, and was found to be stealing from her, so he was discharged. Later on my only little sister, Pauline, strangely disappeared, and could never be found. It was believed at the time that Jasper in a spirit of revenge had stolen the little child, but he could not be located; and the grief of that loss I really believe hastened the death of my dear mother.”

Thad was so overcome with emotion that he could not go on. His chums cast sympathetic looks at him, for they were very fond of their leader; then Allan Hollister took up the narrative by saying:

“And his gentleman who happened to glimpse the man and girl, and who had known of the circumstances in the past, wrote that he felt almost certain he had been looking on the face of the long-lost little Brewster girl. Daddy was laid up with one of his attacks of rheumatism; and besides, he could never have stood such a trip. So he put up an unlimited amount of spending money, enough to allow the whole patrol to make the trip by rail; and here we are, determined to stand by our chum, and penetrate this dismal Louisiana swamp to find out whether it is Thad’s sister and Felix Jasper who are living somewhere about here; or if the gentleman made a bad mistake.”

“Yes,” went on Bob White, impulsively, for he was a true, warm-hearted Southern boy, a little touchy with regard to his “honor,” but a splendid and loyal comrade for all that, “and we’re bound to do it, I reckon, suh, or know the reason why.”

“The first thing we did when we got down here,” Giraffe went on to say, “was to pick up all the information connected with this swamp we could, which was not a great lot, because they seem to think it’s a terrible place, and few persons ever dream of penetrating its unexplored depths, except now and then a muskrat trapper, or an alligator-skin collector; though they do say it’s been an asylum for occasional negro convicts who broke away from the turpentine camps and were pursued by the dogs.”

“Huh! looks some like we might be up against the toughest proposition we ever tackled, believe me,” Step Hen observed.

“Well,” remarked Bumpus, composedly, “we’ve pretty nearly always come out on top, haven’t we; and according to my notion we’re strong enough to do it again.”

“There’s something pretty strong around here, and that’s a fact,” spoke up Giraffe as he changed his seat. “I wonder, now, if the decaying vegetation in these here old Louisiana swamps always tone up the air like that. Smells to me kind of like rank onions that have got past the useful and respectable stage. I can see how we’re bound to have a high old time if this is a specimen of swamp air, and we expect to breathe it for mebbe two whole weeks.”

“Oh! say, that ain’t hardly fair!” remarked Davy Jones; “alaying it all on the poor old swamp, when, honest Injun, I’ve been asniffing that same queer odor all day.”

He looked straight and hard at Bumpus as he said this. The fat scout immediately frowned as though he felt hurt.

“I know what you’re ahinting at, Davy Jones,” he remarked, hotly; “just because I choose to continue wearing my old suit, and keep the new one for another day you like to make out this outfit ain’t all right. I admit she looks a mite greasy, because I’ve helped cook many a fine meal while wearing the same. There’s associations wrapped up with every inch of this faded cloth, and you can laugh all you want to, but I decline to throw it away while on this trip. What’s a swamp but a muddy hole, and I don’t choose to spoil my brand new suit, if you do. Besides, Step Hen and me, we’ve got such stuffy colds in our heads we can’t smell a single thing.”

“Then for goodness sake, change places with me, and be a chum of Step Hen’s during the remainder of this whole trip. Besides,” added Giraffe, as he saw Bumpus getting as red as a turkey gobbler with indignation, “it’ll balance the two boats better, I’m thinking. How about that, Mr. Scout-master?”

“I was figuring that we could do better than we have so far; and if Bumpus is willing to change with you, let him,” replied Thad. “That will bring him in my boat with Davy and Step Hen. They say colds like that are catching, so perhaps both Davy and myself will soon have one.”

“Huh! I hope so,” muttered the Jones boy, sniffing the air suspiciously when poor Bumpus happened to move to windward of him; but the usually good-natured fat boy pretended not to notice the slur.

“Well, as we’re all through lunch, let’s make a start, for we expect to be deep in Alligator swamp long before night comes on,” said Allan, who had the second paddling boat, fashioned somewhat after the pattern of the old-fashioned dug-out canoe made from a log, in his charge, being the assistant patrol leader of the Silver Fox band.

Ten minutes later, and having packed all their stuff away, the boys were ready to continue their journey into the depths of the thickening wilderness where the hanging Spanish moss that draped the trees proved such a strange sight to them all, and gave such a graveyard look to their surroundings that more than one of them felt a little shiver of apprehension, as though they fancied all manner of mysteries must presently arise to confront them.

The boat containing Giraffe, Allan, Bob White and Smithy happened to be ahead when they came to where their progress was hindered somewhat by floating logs and other stuff; so Giraffe, without being told to do the same, stood up in the bow to punch his way clear. He made a vicious stab at what he thought was a floating log, but had no sooner struck his paddle against it than the seemingly harmless object made a sudden lunge, splashed water all over the boat, and disappeared from sight; while the astonished boy, losing his balance as his paddle slipped off the scaly armor of the old mossback alligator that had been sleeping so placidly on the surface of the lagoon that it had not noticed their approach, fell in with a tremendous splurge.

“Alligator!” shrieked Smithy; and as this was the very first saurian he had ever set eyes on, not in confinement, his excitement was hardly to be wondered at.

“Lookout, Giraffe, he’s after you!” cried Bumpus, from the other boat, close by.

There was no need of spurring the lanky scout on to any further exertions; for he had comprehended that the living log was a scaly reptile, even before he took that involuntary bath; and the instant that his head came above the surface again he made frantic haste to clamber back into the boat.

Allan had instantly stooped, and possessed himself of a repeating Marlin rifle, which he kept handy at all times now; and had that ’gator attempted anything like hostile action, the chances were that he must speedily have made the acquaintance of a soft-nosed bullet that would probably have finished his earthly career in a hurry.

No doubt the denizen of the swamp was even more badly frightened than Giraffe, for after that one whirl and splash nobody ever saw him more. But then, how was the lanky scout to know that? Imagination peopled that dark waters with a myriad of twelve-foot ’gators, all plunging toward the spot where he was struggling to drag himself back into the boat, though his soaked garments seemed to weigh very nearly a whole ton.

“Lookout, Giraffe, or you’ll upset us all!” shouted Bob White, who probably did not see any great reason for all this haste, because conditions always color such things differently.

“Help me in, somebody, can’t you?” gasped the clinging boy. “Want to see me bit in half, do you? Thad, you lend me a hand, since these other fellows won’t? Oh! what was that?” as a great splash was heard; but of course it was only Bumpus playfully striking at the water with the flat of his paddle, on pretense of “shooing” away the sportive and hungry alligator, though no doubt he had also in mind the idea of hastening Giraffe’s getting over the gunwale on wings of fear.

They managed to pull him aboard, where he stood looking all around, as though in the end a trifle disappointed not to see a few monsters showing their keen regret at being cheated out of a meal; for that would have always added flavor to the story when he came to tell it.

“Guess he’s gone down to the bottom!” suggested Giraffe; “I kicked with all my might all the time I was in the water, and that’s the only way to scare a ’gator, a coon told me. But you can laugh all you’ve a mind to, Step Hen and Bumpus, I reckon you’d a done as much as I did if it’d been you fell in. Why, I saw him open his jaws, and I declare to goodness, he had a mouth big enough to swallow a sugar barrel, and that’s the honest truth, fellows.”

“I see plain enough that we’re due for some rattling lively times while we’re down in old Louisiana,“ remarked Smithy. “But if you don’t mind, Thad, please paddle your craft a little more to the left, because the breeze is blowing straight from you to us, and, well, you know what I mean.”

Bumpus was feeling so hilarious over seeing that great splash taken by his persecutor, Giraffe, that he did not pay the slightest attention to what Smithy said.

“You know, fellows,” the fat scout went on to remark, “up to now it’s been poor old Bumpus who’s generally gone overboard, or got in trouble like that; but seems as if times have changed, and now Giraffe, he wants to take his turn. If I’d been close enough, and had a boat-hook handy, sure I’d a got it fast in the collar of your jacket, Giraffe. And I’d a considered it a pleasure, too.”

“That’s right, I reckon you would, Bumpus; you’re an awful accommodating chum, ain’t you?” the tall scout sneered. “But see here, whatever am I to do now, Thad?”

“Sit in the sun, and let your duds dry on you!” suggested one comrade.

“The only trouble is, we have to bail out the boat, because he’s nearly flooded us right now,” Bob White asserted, beginning to get busy with a big sponge.

“Had I ought to make a change, Thad?” demanded Giraffe, ignoring these side thrusts, and appealing to the fountain head.

“Just suit yourself,” replied the scout-master.

“That’s what I mean to do, only this is my new suit, and I kinder hate to put it up to dry, for fear it’ll shrink on me, and I can’t get out of it again,” the lanky one went on to say.

Presently, as the air under the trees was not so warm as if they had had more sunshine, and Giraffe commenced to shiver, Thad told him he had better make the change.

“You can wear your old suit right along, if you have to,” he remarked; “and even if you have to throw away the other, better do that than get a heavy cold from trying to let it dry on you. That’s all very well in hot August weather; but there’s a little tang in the air, even away down South here, along in December. So strip to the skin, and make yourself comfortable.”

Giraffe concluded that after all this was the best policy; and so he set to work, paying little heed to the jests of his chums, who, like all boys, could never let so good a chance to joke an unlucky companion pass by.

“Next time you see a log, Giraffe,” Bumpus told him, “take a second look before you go to punch it with your paddle. They say logs down here have got teeth, and can take a big bite right out of an oar. We don’t want to lose any of our paddles; and let me warn you that it’s risky jumping overboard after one when you do drop it in the drink. We’d hate to see you make a meal for a hungry ’gator; though for that matter it’d be a pretty slim dinner he’d get!”

“Well, one thing sure,” retorted the tall scout, who was now fully dressed, and feeling in readiness to do battle again; “I wouldn’t blame any old ’gator if he declined to gobble you for a relish right now, and that’s what.”

“There you go again, but on account of your recent trouble I’ll let it pass. A fellow that has just been nearly scared to death ain’t responsible for half he says,” and the fat boy waved his hand toward the other as though he really meant it.

“From the way you’ve been pestering us lately about that stuff you forgot to take home to your mother from the drug store, I’d think you had troubles of your own to bother about,” retorted Giraffe. “I never saw such a fellow to keep thinking of little things that don’t amount to a row of beans. Why, you admit it only cost five cents, and yet to hear you let out a howl about it every little while, you’d think it was worth a whole dollar.”

“It ain’t that,” said Bumpus, with dignity, “but I’m so built that when anything gets on my nerves like that has, I just can’t sleep till I’ve solved the puzzle. Did I take that little package home and give it to my mother, or did I leave it anywhere on the way? That’s the question I’d like to have solved; and I mean it shall be, if I have to write to three separate boys whose houses I stopped in on my way home, to tell ’em what a ge-lorious time I expected to have down here.”

“But you did write to your mother from Memphis, to ask her about it; and when we got letters back at that last town you nearly took a fit because there wasn’t any for you,” Davy Jones went on to say, taking a hand in the affair, though he was as far away from Bumpus in the other end of the boat as he could possibly get.

“That’s all very true,” replied the fat scout, composedly; “and now I’ve got to just hold in, and wait a long time till we get more mail. It bothers me more’n words can tell you. A scout should never fail in his duty; and my mother said she wanted what she wrote on that paper the worst kind. What if it was only five cents; I’m not thinking of the amount, but the fulfilling of my duty. Thad always says that’s the main thing to consider. Faithful in little things, is my motto.”

“Hear! hear!” cheered Bob White, from the other boat.

“Good boy, Bumpus! them’s our sentiments, too!” declared Step Hen, hilariously.

“Huh! little things, hey?” sniffed Giraffe; “please get busy fellows, and draw ahead of our friends in the other boat once more. Seems to me the air is better up ahead.”

“But make him beware of the logs, mind you,” called Bumpus, as a parting shot.

They proceeded carefully along for some time. The channel they were following seemed to be very winding, and yet there could be no reasonable doubt but that it was constantly taking the expedition deeper into the great Alligator Swamp all the time.

Thad had tried to get all the information possible about the strange place he intended to visit, but few people could assist him. One man gladly allowed him to have a very rude chart that he said “Alligator” Smith, who made a practice of hunting the denizens of the swamp for their skins, had once drawn for him, with a bit of charcoal, and a piece of wrapping paper. This was when the “cracker” had lost a heifer which he suspected had either strayed into the fastnesses of the swamp; or else been killed, and eaten by some “hideout” escaped convicts, who found a refuge from pursuit within the almost impenetrable depths of the extensive morass.

There were things about this chart which none of them could fully grasp. Thad had some hopes of being fortunate enough to come upon the man who had drawn it, as he was said to be somewhere about, pursuing his queer vocation of acquiring a living from securing the skins of alligators he managed to shoot or trap.

And it was in this way that the eight chums had actually dared to start into one of the least known places in the whole State of Louisiana. Some of those with whom they had spoken about their intended trip had warned them not to attempt such a risky thing without a guide. But Thad was fairly wild to learn whether there could be any truth in the strange story that had come to his guardian in that letter; and he just felt that he could not stand the suspense another day.

Inquiry had developed the fact that inside of the last few months a man and a little girl had really been seen several times, though nobody knew where he stayed; and some said they had seen him paddling out of the swamp in a pirogue, which had evidently been fashioned from the trunk of a big tree with considerable skill.

As the afternoon advanced, and they found themselves getting deeper and deeper in the gloomy swamp, the boys began to realize that this singular expedition might not turn out to be such a pleasant picnic after all. There was always a peril hovering over them that must not be lightly treated; and this was the danger of losing themselves in those winding channels; for they had been told that more than once men had gone into Alligator Swamp never to be seen again by their fellows.

Thad and Allan had arranged a plan whereby they might mark their way; and if it came to the worst they would stand a chance of returning over the same passages that they were following in entering the place.

They did this first by attaching a small white piece of cloth to a bush while still in sight of the last one that had been marked. When these finally gave out they proceeded to break a branch, and allow it to hang in a certain way that was bound to catch their eye, and tell them how to paddle in order to keep passing along the chain.

This was a well-known method among woodsmen in these great swamps, where one can be turned around so easily, and all things look so much alike that even the best of experienced paddlers may make mistakes that are apt to cost dearly.

The boys fell quiet as the shadows lengthened. To tell the truth all of them were growing a bit tired from this constant paddling, and twisting their heads in trying to see so many sights at once; and when Giraffe hinted broadly that in his opinion he thought it might be high time they picked out some nice spot for stopping over, so that the fire could be started, and supper gotten underway, nearly all the rest gave him a smile of encouragement.

“Just what I was thinking about myself,” said Thad; “and unless I’m mistaken, right now I glimpse the place we’re looking for; because, you understand, we ought to have a good high and dry spot for a camp.”

“Do you know whether these here ’gators can climb, Thad?” asked the fat scout, a little nervously.

“Not a tree, certain sure, Bumpus, so you’re safe, if you only show enough speed in getting up among the branches; but they just love to slide down banks, they say, and don’t you go to depending on any such to keep your scaly friends from sharing your blanket,” Davy remarked, maliciously.

“Oh! who’s afraid; not me?” sang out Bumpus, puffing out his chest as he spoke; “besides, haven’t I got a gun along with me this trip; and some of you happen to know that I can use the same. I’ve got a few crack shots to my credit, ain’t I, Thad?”

Before the scout-master could either affirm or deny this assertion, Giraffe gave a loud yell, and was seen to be standing up in his boat, pointing wildly ahead.

“Looky there, would you, boys!” he cried; “that’s a coon in the boat, seems like to me, and he’s paddling like everything to get away from us. What say, shall we give chase, and see if four pair of arms are better than one? Maybe, now, it’s only a hideout darky, scared nigh to death athinking we’re the soldiers come hunting after him. And then again, how d’we know that it mightn’t be Felix himself; because, you remember, they did say he was burnt as brown as mahogany! Whoop! see him make that paddle fairly burn the air; and ain’t he flying to beat the band, though? Thad, why don’t you give the word to chase after him, when you can see we’re all crazy to let out top-notch speed.”

“Hold up!” called out Thad.

Of course, as the scout-master, his word had to be recognized as law by the members of Cranford Troop. Several of the boys manifested signs of disappointment, and impulsive Giraffe seemed to be the chief offender.

As a rule they were not averse to giving vent to their feelings; for besides being Boy Scouts, they had long been school chums.

“Oh! that’s too bad, now, Thad,” Giraffe remarked, dejectedly; “you didn’t want us to chase after that fellow. Four of us ought to’ve been able to beat him in a furious dash; and how d’we know but what it isn’t the very man we’ve come all the way from Cranford to see?”

“It’s too late now, anyway!” observed Bumpus.

“Yes, he’s disappearing among the shadows yonder,” said Davy, who had sharp eyesight; “and I saw him turn to look back at us just when he was passing through that bar of sunlight that crosses the water.”

“Did you think he was a negro, or a white man, Davy?” asked Thad, quietly.

“Well, to tell you the truth, Thad, I guess now he was a coon, all right. He didn’t have any hat on, and his hair seemed woolly enough,” Davy admitted, frankly.

“I thought as much all along,” Thad told them, “and that was one of the reasons I wouldn’t give the word to pursue him. There were plenty of others, though.”

“Name a few, Mr. Scout-master,” requested Giraffe, still unconvinced.

“Oh! well, for instance, we’re all pretty tired as it is, and to make that dash would wear us out. Then we’d lose the chance for camping on this spot here that I picked out, and we might go a long way without running across as good a one. And if it was a black outlaw, one of those desperate escaped convicts from the turpentine camps, if they have them in Louisiana, even should we manage to overtake him he might happen to have a gun of some kind. You could hardly blame him for showing fight, Giraffe.”

“Not when you remember that we’re wearing uniforms pretty much like the National Guard, and chances are he believed we were real soldiers, not tin ones,” was the contribution of Step Hen, easily convinced, after he had given the subject a little reflection.

“Besides,” added Bumpus, as a clincher that he knew would catch the lanky scout; “it’s nearly time we’re thinking of having supper; and sure, it would be too bad if we had to postpone trying that delicious home-cured ham we fetched along.”

The frown left the forehead of Giraffe like magic, and in its place came a most heavenly smile.

“I surrender, boys!” he announced. “I throw up my hands, and give in. Seems like everybody’s against me, and seven to one is big odds. Must be I’m mistaken. If it was a genuine coon after all, why, sure we’d a been silly to waste our precious muscle achasing after him. Besides, looks like the shadows are acreeping out along there, and we’d as like as not get lost somehow. Oh! you’re right, as usual, Mr. Scout-master. I’m always letting my ambition run away with my horse sense. Seems like I never open my mouth but I put my foot in it, somehow.”

“Then why don’t you get a button, and keep it shut?” asked Bumpus, promptly.

“I would, if it was the size of some I’ve known,” responded Giraffe.

“I hope now, you ain’t making wicked comparisons?” the fat scout demanded.

“Why, you don’t think I’d be guilty of such unbrotherly kindness, do you?” was Giraffe’s perplexing rejoinder; and knowing that he could not get the better of the tall scout Bumpus gave a grunt, and stopped short.

They were soon busily engaged in making preparations for camping. Having come all the way from home with the idea of spending some time in the Southern swamp, looking for those whom Thad so earnestly wished to meet face to face, the lads had of course made ample preparations for having at least a fair degree of comfort.

None of them had ever been in the Far South, so all they knew about the country, its animals, and the habits of its people, must come through reading, and observation as they went along.

But they did know the comfort of a tight waterproof canvas tent in case of a heavy rain storm; and consequently a good part of the luggage they carried in the three trunks had been a couple of such coverings, besides the usual camp outfit about which many happy associations of the past were clinging.

These trunks had of course been left in the small town where they had obtained the roughly made canoes, to be picked up on their return later.

Long experience had made every one of them clever hands at tent-raising; and from the way Smithy and Davy undertook to get one up in advance of Step Hen and Bob White, it was plain to see that the old-time spirit of rivalry still held good.

Giraffe as usual took it upon himself to start the cooking fire. He was what the other boys called a “crank” at fire-building, and had long ago demonstrated his ability to start a blaze without a single match, by any one of several ancient methods, such as using a little bow that twirled a sharp-pointed stick so rapidly in a wooden socket that a spark was generated, which in turn quickly communicated to a minute amount of inflammable material, and was then coaxed along until a fire resulted.

Bumpus always stood ready to assist in the cooking operations; because there were so many other things coming along that required dexterity and agility, and from which his size and clumsiness debarred him, that he just felt as though he must be doing something in order to shoulder his share of the work.

As the twilight quickly deepened into night—for in the South there is not a very long interval between the going down of the sun, and the pinning of the curtains of darkness—the scene became quite an animated one, with eight lively lads moving around, each fulfilling some self-imposed duty that would add to the comfort and happiness of the patrol in camp.

And when that “delicious home-cured ham” that Bumpus had spoken of, and which had really come from his own house, so that he knew what he was saying when thus describing it, began to turn a rich brown in the pair of generous frying-pans, giving out a most appetizing odor; together with the coffee that Bumpus himself had kept charge of, well, the healthy boy who could keep from counting the minutes until summoned to that glorious feast would have been a strange combination.

Bumpus was trying a new way with his coffee. Heretofore he had simply placed it in the cold water, and brought this to a boil, keeping it going for five minutes or more. Now he had the water boiling, and just poured in the coffee, previously wetted, and with an egg broken into the same; after which he gave it about a minute to boil, then let it steep alongside the fire for the rest of the time.

“Better than anything we ever had, isn’t it, fellows?” he demanded, after he had tested the contents of his big tin cup, and nearly scalded his mouth in his eagerness. “Ketch me going back to the old way again. Coffee boiled is coffee spoiled, I read in our cook book at home.”

It was good, but all the same Giraffe, as well as several others, declared they preferred the old way, because it was such fun to see if the cook was caught napping, and allowed the pot to boil over; besides, the aroma as it sent out clouds of steam was worth a whole lot to hungry lads.

“Bumpus, I’ve got a favor to ask you,” said Davy, as they started to settle down around the fire, each in a picked position.

“Go ahead, Davy, you know I’m the most accommodating fellow in the bunch. Tell me what I can do for you,” replied the fat scout, immediately; and every word he spoke was actual truth, too, as his comrades would have willingly testified if put on the witness stand.

“I wish you’d let me sit over there, and you take my seat, which, I reckon is much more comfortable than yours; and besides, you complained of a pain in your back, and I’m afraid of the chilly night wind taking you there. You’ll face it here instead.”

“Don’t you budge, Bumpus!” exclaimed Giraffe; “he’s only giving you a little taffy, don’t you see? Thinks he’ll have a better chance to enjoy his grub if the wind don’t blow from you, to him. I wouldn’t stand for it, Bumpus; you just stay where you are. Reckon you look comfortable enough, and what’s the use dodging all around?”

“Huh! guess you’re thinking of your own comfort now, Giraffe,” grunted Davy in disgust.

Bumpus eyed them both in distrust.

“I remember we learned in school that it was best policy to keep an eye on the Greeks that come bearing gifts,” he wheezed; “and so I’ll just stay where I am. If you don’t like it, Davy, why, there’s plenty of space all around. As if I’m to blame because this old swamp isn’t the sweetest place agoing.”

The conversation soon became animated and general, so that the three disputants forgot the cause of their trouble. Bumpus was the bugler of the troop, and always insisted on carrying the silver-tongued emblem of his office along with him; he had it by his side now; but Thad had given peremptory orders that he should not make any use of the instrument except by special order; or under conditions that might arise, whereby they would need to be called together, like a scattered covey of “pa’tridges,” as quail are universally designated in the South.

“We must remember,” Thad went on to say, “that this isn’t just an ordinary jaunt, or an outing for fun. It means a whole lot to me that I manage to find the man and the little girl. Either it will turn out to be Felix Jasper and my lost sister; or else we’ll prove that the gentleman was terribly mistaken. And you can understand, fellows, what a load I’m laboring under all the time that puzzle remains unsolved. But I want you to remember that we ought to keep as quiet as we can. Bumpus, you understand the situation, and why we don’t ask you to amuse us with some of your fine songs?”

Bumpus had a very good voice, and often did entertain his chums while in camp by singing certain songs they were particularly fond of. He was a sensible fellow, and did not take offense easily. Moreover, even though he might feel huffed over some action on the part of his mates, he never “let the sun go down on his wrath,” but was quick to extend the olive branch of peace.

“Sure I understand, Thad!” he declared; “and I’m going to bottle up my voice on this occasion, so’s to have it in fine trim, to let loose in a hallelujah when we find that it is your little sister Pauline—”

Bumpus said no more, and for a very good reason; because, just at that particular moment there arose the strangest sort of sound from some point close by, such as none of the scouts could ever remember hearing before.

“What d’ye call that, now?” exclaimed Step Hen.

Giraffe assumed a superior air, as he hastened to remark:

“Next time you hear an old alligator bull bellow, you’ll recognize the same; but to tell the truth, I’m kind of disappointed, myself, because I expected to get something bigger’n that.”

“Was it an alligator, Thad?” demanded Davy; while Bumpus was seen to involuntarily move a little closer to the tree under which the camp-fire had been made, and the twin, khaki-colored, waterproof tents erected.

The scout-master shook his head in the negative.

“Giraffe’s got another guess coming to him this time,” he said. “From all I’ve picked up, I reckon we’ll not be disappointed when we do hear some old scaly bull bellow. But they tell me this happens generally along toward dawn. And the sound is more like the roaring of a lion, than what a regular bull gives out.”

“But what was that we heard, then, Thad?” persisted Step Hen; for long ago these boys had taken it for granted that a scout-master should be in the nature of a “walking encyclopedia,” as Bumpus called it, filled to the brim with general information on every known topic, and ready and willing to impart the same to the balance of the patrol on request; and truth to tell they seldom caught Thad Brewster in a hole.

“Well, now, there are a lot of things in a Southern swamp, any one of which might make a noise like that. If you asked me my plain opinion I’d guess it might have been a wandering night heron, which has a hoarse cry, some of you happen to know, because we struck them up in Maine that time we spent a vacation there.”

“What other creatures are we likely to run across here, besides snakes and alligators, runaway coons and the like?” pursued Davy, always wanting to know.

“Of course there are muskrats, because you can find them in every swamp east and west, north and south,” Giraffe ventured.

“Yes, muskrats are found, though not so many as in the north, and the skins are sometimes hardly worth taking. But there are plenty of raccoons and ’possums: and I’m told they get quite some otter down here, the most valuable pelt that comes up from the South, selling at something like seven dollars a skin.”

“Whew! that’s talking some,” muttered the interested Bumpus. “Did I ever tell you fellows that I once had a great notion of starting in to be a trapper? Yes, I even read up a whole lot about it, but kinder got twisted in the directions of how to go about things, so as not to let the cunning little varmints get the human odor.”

At that there was a general laugh, causing the fat scout to look around indignantly; whereupon the others, notably Step Hen, Davy and Giraffe exchanged winks.

“Ain’t that so, Thad?” demanded Bumpus, turning to the scout-master.

“You’re right about that, Bumpus,” came the reply. “Allan here, who has had lots of experience, will tell you that the most successful trapper is the man who manages somehow to keep from alarming his intended game, both by making few if any tracks around the place where he’s put his trap; and by eliminating the human odor that their sensitive noses detect.”

“There, didn’t I tell you?” demanded Bumpus, triumphantly. “Think you’re smart to just sit there and chuckle; but you’ve all got heaps and heaps to learn about the secrets of the woods. I know my own weakness, and I’m studying hard, trying to remedy it. You’d never guess what a lot of cute things them pelt-takers have to put up, in order to fool the woods folks; ain’t that a fact, Thad?”

Bumpus knew that so long as he could get the scout-master to corroborate all of his statements he was sure of having his opponents in a hole; and it was amusing to see how he managed to accomplish this same thing.

“Yes, it’s all mighty interesting,” Thad assured them. “Nowadays nearly every up-to-date trapper makes use of a prepared scent which he places on the trap, even if he baits the same. It is sold by dealers in skins; and they say a trapper can get much better results by using this, to attract the little fur-bearing animals.”

“What’s that, Thad; you tell us they sell this scent to trappers, or such as think they have a call in that direction?” demanded Giraffe, suddenly.

“Of course any one can buy any quantity, if he’s got the price,” Thad assured him. “You seem interested, Giraffe; perhaps, now, you’re thinking of embarking in the game?”

But the lanky one only shook his head, and turning on Bumpus he demanded severely:

“Looky here, Bumpus, did you, when you read up about all these here interesting things connected with trapping the fur-bearing animals of the wilderness, ever go so far as to invest a dollar in buying any of this wonderful stuff that they say is so fetching that the silly little beasts just can’t resist it?” and as he said this Giraffe tried to hold the fat boy transfixed with his piercing gaze—some of them had at one time even called Giraffe “Old Eagle Eye,” earlier readers of these stories may remember.

“No, I didn’t, if you want to know, Giraffe!” Bumpus broke out with; “and I ain’t agoing to tell you any more about what I learned; because you’re all the time apicking on me, and accusing me of things. I know I make mistakes sometimes, and that one about not remembering whether I fetched my mother back the medicine she wanted is abothering me like everything right now; but the rest of you are in the same boat, ain’t you? Here was Giraffe just a little while back awanting to rush after that runaway convict, just as if we had lost anything like that. Course it was a mistake and chances are we’d got in no end of trouble if he’d had his way. Oh! everybody blunders sometimes; to-day it may be poor old Bumpus; but to-morrow one of the rest of you is in the soup. Forget it, now.”

“What about these swamp animals, Thad, or Allan; and why do you say the skins don’t bring as good prices when they’re taken down here, as in the North?” Step Hen wanted to know.

“Don’t it stand to reason that the colder the country the thicker the fur Nature gives to the animals that bear it?” asked Allan.

“Why, yes, seems like that ought to be so; and I guess that must be the reason Canada skins bring the best prices of all,” Giraffe admitted.

“Sometimes three times as much as ones taken far South,” Allan told him.

“I’ve no doubt that sooner or later we’ll find chances to examine the tracks of ’coons, ’possums, foxes, muskrats, and even otter, while we’re looking around,” Thad remarked; “and it’ll be interesting to notice what difference there is between the various animals, as well as between the same breed up in Maine and down here in Louisiana; for they grow smaller, as a rule, the further south you go. A Florida deer can be toted back to camp on the back of the average hunter, while one up in Michigan or the Adirondacks would need two men and a pole to carry it any distance.”

“This sure is mighty interesting,” observed Step Hen. “I’m always ready to soak in information connected with the woods. I’m like a big sponge, you might say; ready to give it out again on being squeezed.”

“On my part,” Giraffe mentioned, “I don’t seem able to get that coon out of my head; because, if he was what we think, a hideout escaped convict, chances are he must want a whole lot of things, from a blanket, gun and clothes, to grub.”

“That’s unkind of you, Giraffe, to bother us with such gloomy thoughts just as we are thinking of soon going to bed,” remarked Bumpus, uneasily.

“But there’s some horse sense in what he says, don’t you forget it, Bumpus,” pursued Davy.

“That’s a fact,” added Step Hen. “Just put yourself in his place for a while, and try to imagine what your feelings’d be like, asneaking around a camp of boys, nearly half starved at the same time, and scenting the good smells that fill the air all around—of course I mean cooking meat, coffee and the like. Say, wouldn’t it nearly set you crazy; and honest now, Bumpus, don’t you think you’d take some risks to try and hook what you wanted so bad?”

Bumpus, upon being thus deliberately appealed to, nodded his head in the affirmative, and remarked:

“I sure would, and that’s a fact, fellows. Then you kinder look for a visitor in camp to-night, do you? And that means everybody’s just got to sit up and stand guard, don’t it? all right, you’ll find me as willing and ready as ever to sacrifice my comfort for the public welfare. I’m always there with the goods.”

“Hear! hear! Bumpus, we all know you like a book!” declared Step Hen, pretending to clap his hands in enthusiasm, though no sound resulted from the action.

“Yes, and if the will was father to the deed, there’d be nothing left undone while Bumpus was around; for he’s always ready to try his best,” Allan went on to say, while the object of all this praise turned rosy red with embarrassment.

“Mebbe you’re only joshing me, boys,” he remarked uneasily, “but I’m taking it for granted that you mean all you say, and believe me, I’m grateful. If I wasn’t so full of supper I’d get on my feet, put my hand on my stomach this way, and make you the best bow I knew how. Like a lot more of things you’ll have to take the intention for the deed there, too. It’s a case of the spirit being willing, but the flesh weak.”

“Well,” said Giraffe, “I didn’t know that there was anything weak about you, Bumpus; but never mind starting an argument about it now. We’ll just arrange things so that two scouts are on duty all the time through the night. How would that suit you, Mr. Scout-master?”

“Just about right,” replied Thad; “because we are now eight, all told, and that would allow us to divide up into four watches. And as Bumpus is so anxious to do his whole duty by the camp, I’ll promise to take him on as my side partner when my turn comes.”

“Well,” mused Giraffe, “it’s mighty nice to have a fellow along who isn’t afraid of anything, and will even make a martyr of himself in order to keep peace in the camp.”

“P’raps you wouldn’t mind explaining just what you mean by that, Giraffe?” the stout scout quickly remarked, suspiciously.

“Oh! you’re as touchy as wildfire, to-night, Bumpus,” retorted the other, with a chuckle, as though he felt that he had attained his object, which was to excite the curiosity of the fat boy. “Just turn your mind on what may happen while we sleep, and you’ll be happier. But here’s hoping that breeze keeps acoming from that same quarter all the night, because then we can plan better.”

Davy snickered audibly at this, but Bumpus assumed a lofty air, and would not pay any further attention to those who were evidently bent on badgering him.

“How will we pair off for the tents?” asked Bob White, presently.

“I think it would be just as well to keep the formation we already have in the boats,” the scoutmaster immediately replied, as though he might have already figured this out.

Davy Jones was heard to give a disappointed grunt, though just why he should be the only one to do so must remain a mystery; but at any rate Bumpus refused to let himself show that he took it as personally directed toward him.

“That means Giraffe, Bob White and Smithy sleep in Number Two along with me, does it, Mr. Scout-master?” Allan inquired.

“Yes, and let Smithy pair off with you, while Bob White and Giraffe are pards on guard. I’ll take the first stage, with Bumpus, because that’ll let him have a longer uninterrupted sleep, and he’s more apt to stay awake in the earlier part of the night than later on. When the time is up we’ll arouse Giraffe, who’ll take charge of his watch. That’s understood, is it?”

All of them declared it was very simple; and that surely a spell of less than two hours could not turn out to be a very hard task. Even Bumpus was apparently grimly resolved to show his mates that he had “reformed,” and would never, never again be guilty of such a crime as going to sleep while playing the part of sentry.

“You’ve got me so worked up atalking all about that black escaped jail bird,” he stoutly affirmed, “that chances are my eyes won’t go shut the whole night long. You see, I’m sensitive by nature, and when I hear dreadful things, like that poor fellow nearly starving while he’s hiding out in the swamp, with the dogs trying to get on his trail all the time, it makes my flesh creep. So please, Giraffe, don’t say anything more about it. You get on my nerves.”

“Huh! that ain’t a circumstance to some things—” began the tall scout; and then as though suddenly thinking better of it, he cut his sentence off short, so that no one ever knew what he had meant to say, though there was Davy chuckling again, just as if he might have a strong suspicion.

They had soon arranged their blankets in the two dun-colored tents. The canvas had been prepared by tanning in some manner, so that its former white hue was altered; and at the same time it had been rendered impregnable to water. This is a fine thing about these prepared tents; because the ordinary covering, while it is capable of shedding rain for some time, once it gets soaked, if you simply touch it on the inside with your finger, you are apt to start a dripping that nothing can stop as long as the rain comes down.

Giraffe, who was very angular, and always complained of feeling every little pebble or root under his blanket, when out camping, at once started to gather some of the hanging Spanish moss, to “pad his bed with.”

“They tell me it makes fine mattresses, after it’s dried,” he remarked; “so p’raps it’ll keep me from wearing a hole in my skin while I rest here. Say, it’s simply great, let me tell you,” he added, as he sank down to test his puffy couch, “so I’d advise every one of you to get busy, and lay in a supply.”

“How about insects of all kinds, from red bugs to ticks?” asked Step Hen, who already had a few fiery spots on his lower limbs, marking the places where some of the former invisible guests had buried themselves, and started to create an intolerable itching and burning that made him scratch frequently, without much alleviation of the trouble.

“Oh! who cares about such small pests as them?” remarked Giraffe, loftily.

“Not much danger, if you select clean moss, Step Hen,” Thad told him; and as the scout-master was himself following the example set by the inventive Giraffe, of course all the others copied after him.

“Misery likes company, they say,” Step Hen was heard to mutter; “and p’raps now to-morrow there’ll be the greatest old scratching bee you ever did see. As I’m in for it anyway, guess I’ll take the chances of mixin’ the breed,” with which he flung prudence to the winds, and started making a collection for himself.

Now, Thad did not mean to neglect any precaution looking to making sure that if a visitor came to the camp during the night, in the shape of a human black thief, he would find it difficult to carry off any of their possessions.

First of all, he paid particular attention to the boats, the paddles of which he himself carried into the middle of the camp, and finally hid away in the tents, so that they could not easily be run across.

Then he had some of the boys assist him, while he ran the two canoes far up on the shore. Even then he secured the painters in such fashion that any one would have great difficulty in unfastening the same.

“I should think that would make us feel secure about our boats, Thad?” Allan remarked, after all this had been carried out with scrupulous care; for the scout-master believed that what was worth doing at all was worth doing well, and he applied this principle to his every-day life, often to his great advantage.

“If we know what’s good for us we want to always guard the boats above all things,” Thad went on to tell them.

“I should say so,” Bumpus admitted; “just think what a nice pickle we’d find ourselves in, fellows, if we suddenly lost both boats while we were right in the middle of the swamp. We could lose lots of things better than them.”

“Bumpus,” observed Giraffe, solemnly, “you never said truer words—we could; and there might even be some things we’d be glad to part with, but which seem to hang on to us just everlastingly.”

Davy seemed amused at hearing the tall scout say this; but Bumpus either mistook it for a compliment, or else chose to act as if he did; for he grinned, and nodded, and wandered back to the tents to get his gun; for Thad had selected the first watch for himself and his partner.

“I’ll just show ’em that I can stay awake these days,” he was saying to himself in his positive way. “Time may have been when I was just a little mite weak that way; but I’ve reformed, so I have. Huh! what’s two hours to me, I’d like to know?”

Some of the other scouts might, had they chosen, have recalled numerous instances where Bumpus, being set on guard, had later on been found “dead to the world,” committing the most heinous crime known to soldiers in war-time, that of sleeping on post, and thus putting the whole army in peril.

When one fellow started to crawl inside the tent others followed his example, until only Thad and Bumpus remained. The fat scout had to take a firm grip on himself, when he saw them going to their inviting blankets, buoyed up so temptingly by those armfuls of soft gray moss; but he proved equal to the test, for he shouldered his gun, and bade Thad station him in his place.

“You’ll have to stay right here, Bumpus,” the other told him. “I know it isn’t the most inviting spot going, for the ground is wet, and you can hardly find a place to stand on; but those things are good for a sentry, because they help keep him awake.”

“Oh! never mind about me, Thad; I’ll prove true blue every time. But where will you hold forth? I ought to know, so I could find you, in case anything suspicious came along.”

So Thad pointed out where he expected to stay, and then went on to warn the other once more:

“Be very careful about using your gun, Bumpus,” he said.

“Oh! I will, sure, Thad,” declared the fat scout, hastily. “I hope now you don’t think I want to have any poor fellow’s blood on my hands, do you? I ain’t half so ferocious as Giraffe, now. You heard what he said about thinking the coon’d get what he deserved, if he came aprowling around here in the night, and somebody filled him chuck full of shot? I don’t look at it that way. Fact is, I’m sorry for the poor wretch; and I’d share my dinner with him, if I had a chance, laugh at me for a silly if you want to.”

“But you don’t hear me laughing at all, Bumpus,” Thad told him; “and I understand just how you feel about it. Nature gave you a tender heart, and made Giraffe on different lines; but I tell you plainly, I’ve often wished some of the other fellows were more like Cornelius Hawtree!”

“Oh! have you, Thad?” said the fat boy, with a suspicious tremor in his voice. “Thank you, thank you ever so much for saying that. I’d rather have your good opinion, than that of any other fellow I ever knew.”

And somehow he felt so light-hearted after receiving that little sincere compliment from the watchful scout-master, that he really found no great difficulty in keeping wide-awake during the entire term of his vigil; for there is nothing equal to a little praise to set a boy thinking, and therefore remaining vigilant.

When the time came to make a change he spoke to Thad as soon as the other drew near his position.

“Never batted an eye once, Thad, and that’s a fact,” he announced, proudly. “Oh! I’m on the road to better things, I tell you. And while I heard lots of queer old grunting and groaning deep in the swamp, I didn’t see a suspicious thing. Will you get Giraffe and Bob White out now?”

“Yes, because they come tailing after us, according to the programme;” and while Thad crept into the second tent to arouse the boys, Bumpus hung around so as to inform Giraffe that he had fulfilled his duties as sentry to the letter.

However, the tall scout seemed to want to hurry past him, and only gave a grunt in reply when Bumpus launched forth on an elaborate account of how he had proved himself equal to the test. In fact, one might have thought that Giraffe was holding his breath as though he feared to take cold by breathing the cool night air too suddenly, after coming out from his snug blanket.

When Thad and Bumpus had also crawled under the flap of the first tent, all immediately became quiet again, the new sentries having taken up their positions as marked out by the patrol leader, in whose hands such things must lie, as he is always in charge of the camp.

Bumpus heard a little restless moving about when he tried to settle down, as if at least one of the other occupants of the tent might be trying to change his position. But the fat scout was too tired and sleepy to bother his head about any trifle like this; besides his cold seemed to get no better, and he was apt to give a loud sneeze at any time.

He distinctly remembered allowing his head to drop on the rude pillow he had fashioned out of his shoes, covered with his clothes-bag; and then seemed to be carried away on the wings of dreams.

His waking up was very sudden, for it seemed to Bumpus that a cannon had been discharged close to his ears, after which came all sorts of loud calling.

When the alarmed Bumpus came crawling hastily out of the tent, he trailed after the other three who had been sleeping near him; for of course, not being forced to carry such a weight around with them as fortune decreed the fat scout should possess, Thad, Step Hen and Davy Jones were much more spry in their movements.

Bumpus found a scene of more or less excitement when he reached the open air.

“I tell you I did shoot the thief, Thad, because I heard him kicking and grunting over there in the bushes,” Giraffe was crying, in excited tones; and no doubt he was shivering all over at the very thought of having done such a thing as fire directly at a human being.

“What was he doing at the time?” demanded the scout-master, who did not altogether like the idea of hearing what the sentry declared was the truth; for his little talk with Bumpus told how Thad felt about the matter.

“Just sneaking right into the camp!” declared Giraffe, who seemed to feel that his act might need bolstering up the best he knew how. “Why, from his actions I just made up my mind the ferocious convict was bent on murdering the lot of us in our sleep, and getting away with everything we had. I tell you it served him right, Thad, and you must know it. I tried to hit him in the leg; but the light was that uncertain a fellow couldn’t just make sure. I hope myself I haven’t done any worse than give him a wound, which you can bandage up.”

Already it seemed, Giraffe’s bold heart was failing him.

“We ought to see about it,” said Allan, who, when there was any unpleasant duty to be performed, never allowed himself to shirk.

“Giraffe, show us where you think he keeled over,” demanded Thad.

“Why, over there where you see them bushes waving in the night wind, whenever the fire picks up. I’ll foller after you, as soon as I can; I’m afraid I sorter sprained my ankle turning so sudden-like after I shot, and it hurts like anything, let me tell you. Go ahead, Thad, and take a light along. If you haven’t got that handy little electric torch, why, just snatch up a stick from the fire. And look out everybody, that he ain’t playing possum, and meaning to shoot when you come close up.”

Of course Thad understood. It was not that Giraffe was growing timid, for he had always been accounted the boldest of the boys in the Silver Fox Patrol; but a sudden sickening realization that by his incautious shot he may have taken a human life, however worthless, made him feel weak about the knees; that talk of a possible sprain of his ankle was a pure fabrication to cover his hesitation about, looking on his work.

Thad, however, would not hold back on that account. If there was a wretched human outcast lying there in pain, the quicker they found this out the better, because, as scouts they had a plain duty to perform.

So Thad sprang over to the smouldering fire. As Giraffe had said, the flames occasionally leaped up as they found new places to eat into the brands; and quickly selecting a promising torch he waved it several times around his head until he had coaxed it to flame forth, when he led the way in the quarter mentioned by Giraffe.

The latter came limping after, no doubt all of a quiver as to what he would hear said in another minute.

“There he is now, lying over yonder!” suddenly gasped Step Hen, pointing; and Bumpus gripped his gun nervously as he tried to crane his fat neck in order to see.

“Yes, there is something lying there!” announced Allan; “and I saw it move just a little then, so I reckon that it’s pretty nearly gone!”

“Oh, that would be tough on the poor critter!” said Bumpus, sympathizingly.

“Yes, and on our chum Giraffe!” echoed Davy, with something about his voice as though he meant to imply that he would not envy the one who had been so hasty about firing at an intruder.

Thad kept right on advancing, and suddenly he was heard to give a queer little hysterical laugh of relief; which proved that the scout-master must have also been laboring under quite a strain.

“Cheer up, Giraffe!” he called out.

“Ain’t he dead, then?” cried the tall scout, forgetting to limp any longer as he started to hurry toward the spot.

“Oh! I guess he’s a goner, as far as that goes,” Thad went on to say; “but it isn’t a man after all, only a runt of a razorback pig!”

“Well, what d’ye think about that, now?” remarked Smithy, as they gathered about the dun-colored victim of Giraffe’s deadly shot; and which had evidently given its last kick, for it was stiffening out even then.

Giraffe was heard to draw several long breaths. He could not say a word at first, emotion so nearly overcame him; but then Thad was glad this had taken place, because he believed it might teach the impulsive one a much needed lesson. Already had Giraffe learned that he had a heart, which was not so callous as he made out. And he would hardly be apt to pull trigger so quickly at another time, when there seemed to be a good chance that it might be a fellow human being at whom his bullet, or load of shot, was to be sent.

“I thought I heard a grunting when I shot,” he finally admitted; “but there were all sorts of sounds breaking out around me. And then you fellows started to yelp like everything, so no wonder I got mixed up some. But see here, Thad, this porker belongs to somebody, don’t he?”

“He certainly must have, when he was alive,” answered the other, with a smile; “and if we can ever learn who his owner was, we’ll be only too glad to settle the bill with him. That may prove to be a dear snap shot you took, Giraffe; because of course the cracker will put a high valuation on his property. They always do when a train kills a cow on the track.”

“Well, it would be a shame to waste such juicy meat, wouldn’t it?” pursued the lanky scout, insinuatingly, as he made his jaws move in a way that carried out the idea of feasting.

“Don’t worry, it isn’t going to be wasted,” said Thad. “If we get the name we’re bound to have the game, too. So hang up your victim by the hind legs, Giraffe, and in the morning we’ll see that we get two fresh hams, some shoulders, and spare ribs in the bargain.”

“Yum! yum! how’s that for high? Nut-fed pork for me every time, fellows. Haven’t I read heaps about the same being so fine down in Old Virginia. Here, give me a hand, will you, Bumpus—no, never mind, one of the others will do as well. Smithy, you take hold, because you’re nearly as tall as I am; and we’ll tie the pig’s hind legs together, so he can hang nicely.”

This was soon accomplished, and all of the scouts felt that the adventure, though giving them something of a shock at first, was not fated to be without its compensating features.

Once more those whose privilege it was to be occupying the twin tents while their comrades remained on guard without, again sought their blankets, and the soft couches fashioned from the yielding gray Spanish moss.

Giraffe, had, however, so far yielded to the dictates of his better nature to say to Thad before the scout-master crept out of sight:

“I want to tell you that I’m awful glad that was only a shoat of a razorback instead of a poor black coon,” which was as good as admitting that he had learned his lesson, and would be much more careful after that how he pulled trigger when he did not exactly know what species of intruder had invaded the camp.

Thad was more than satisfied with the result. He believed that he would not mind being given a frequent shock, if by its means the rest of the boys under his charge might see their way clear to better things.

At the proper time Giraffe came and woke up Step Hen and Davy, who were to take a turn outside. The latter was heard to express himself the very first thing he crawled beyond the flap of the tent that “the night air was quite cool, and likewise very sweet.”

Morning came at last, and there had been no further alarm; but for all that the boys were glad when Thad called them forth, and said it was high time they got breakfast started, as they had a long day’s work before them.

Giraffe begged that Allan cut up the dead pig; and as the Maine boy had had considerable experience along that line, he consented to act as butcher for the occasion. Nothing would do the lanky scout but that they must have some of the razorback in the pan for breakfast, in the shape of chops, for he could not wait until another whole day had passed before tasting, to see if “nut-fed” pork was so very fine after all.

Some of them said they thought it was “peculiar,” others did not fancy it very much; but as for Giraffe, he fairly raved over it; although Davy hinted that he was just “making believe,” so that he could come back three more times for the portions of those who shook their heads, and said it was a little too “piggy” for them.

Bumpus was strangely quiet this morning. He could be seen frowning occasionally, as though his thoughts might not be very pleasant; but then they knew what a great fellow he was to worry over small things; and they took it for granted that he must be again trying to puzzle out the answer to that mystery concerning the little package of medicine—whether he had really delivered it to his mother, or left it at some house on the way home.

No doubt he even pictured that mother as suffering all sorts of agonies just because he had been so careless; for he often declared it was going to be a terrible lesson to him, and break him of some of his bad habits.

But then he also eyed Giraffe and Davy suspiciously whenever they came near him, as though he rather expected to hear them once more make disparaging remarks about the odors they claimed came from the old and greasy suit he insisted on wearing while in the swamp, instead of soiling his brand new one; but they failed to do anything to stir him up, from one reason or another.

“There’s Thad beckoning to us to all come over,” said Step Hen.

“He’s found something or other, I warrant you,” Davy remarked; “because I could see him nosing around. Tracks, chances are ten to one, you mark what I say.”

For once Davy proved a true prophet, for as they came up to where the young scout-master was standing, Thad pointed to the ground, and then went on to remark:

“When you fired that shot, and knocked over the shoat, Giraffe, you builded better than you knew. Look right here, and you’ll see where a man was crawling along on his hands and knees, bent on entering our camp. He must have thought you’d taken a shot at him, for here’s where he whirled around behind this tree, and then made off in a stooping posture as fast as he could move, always trying to keep a clump of bushes between himself and the camp. And the man your shot scared off, Giraffe, was a barefooted escaped convict too, as the signs seem to prove!”

“That’s interesting news, Thad!” Step Hen declared.

“The way you say that makes me think you mean ‘interesting, if true,’” Thad remarked, with a little laugh. “In other words, you want me to prove it.”

“Oh! well, we’re all such a lot of slow-witted scouts that we have to be shown; just like we’d come from Missouri,” admitted the other, in a tone that was meant to serve as an apology.

“And I’m always ready to explain as far as I can,” the scout-master told him. “At the same time I have to keep an eye on Allan here, for you all know that when it comes to reading the signs of the woods I sit at his feet. What I pick up just by figuring out, he knows from past experience. So I want him to pull me in just as quick as he sees I’m on the wrong track; promise that, Allan.”

“Go ahead,” remarked the Maine boy, but his manner told plainly enough that he was very little afraid he would have to do anything of the kind.

“Of course,” Thad began, “all of you can see by the marks here that something was moving along toward our camp; and if you look a little closer you’ll notice that it was a man on his hands and knees; for here are the plain impressions of both his hands; while his shuffling knees made that mark, and that, and here is where his toes dragged along. Plain enough, eh, fellows?”

“As easy to read as A B C!” declared Giraffe, eagerly.

“Another thing is that he had just reached this spot behind the bushes at the time Giraffe let fly with his gun, and then we all started to shout; for you can see the tracks go no further. On the contrary, the man became suddenly frightened, under the belief that he had been discovered; for here he scrambled to his feet, as you can plainly see each impression of a bare foot, and as he hurried away he kept back of the low bushes, from which I deduce the idea that he must have stooped over in order not to be seen and fired on.”

“Well, it goes right along like a book, don’t it?” said Bumpus, looking at the young scout-master in admiration and wonder; for he could not imagine how any one, and a mere boy at that, could discover so much just from observation, and using his common sense at the same time.

Allan nodded his head approvingly.

“But chances are that isn’t near all you noticed, Thad?” he said, questioningly.

“You’re right, it isn’t,” said the other, promptly. “I can see from the signs that the man is barefooted, and consequently in great need; so I am compelled to believe that he must be an escaped convict who has been trying to keep life in his wretched body, perhaps for months, in this swamp, eating roots or berries, trapping birds, or catching fish, muskrats, turtles, anything that he can find. And as nearly all those who are held in these camps are blacks, I find it easy to guess that this is a negro.”

“Ain’t that a great way of finding out things, though?” marveled Bumpus. “Why, Thad, you talk just like you’d been watching that poor old chap every second of the time. I don’t reckon, now, that you could tell us anything else about him—how big he was, and all that?”

“He was a good-sized fellow, for you can see that the track of his bare foot is really tremendous; and if you look here you’ll notice where he lay flat on his face, so that it is possible to roughly measure his length—all of six feet, too. And his left hand is lacking one finger!” added the scoutmaster.

“What’s that?” gasped Step Hen. “You’re only joshing us now, Thad; for how under the sun could you tell such a thing as that?”

Allan chuckled, and looked immensely pleased.

“I thought so!” he was heard to mutter to himself.

“Well, it’s the old story of keeping your eyes about you,” remarked Thad, “and using your head as you go. Three separate times, now, I saw where he had placed his left hand spread out on the ground where it was soft enough to take a pretty good impression; and in every instance the third finger was missing; so with all that proof I thought I was safe in assuming that this man was marked. And let me say, that later on when we get the chance I mean to ask a lot of questions just to satisfy myself about it. If a convict escaped from jail, or some camp, who has no third finger on his left hand I’ll consider that I’ve proved my case.”

Some of the boys were still a little skeptical, and asked to be shown those wonderful imprints of the hand that told Thad such an interesting story; but after they too had examined them they admitted that it was even so.

“It sure beats the Dutch how these things stick up with some fellows,” Bumpus frankly admitted, as he scratched his frowsy head in wonder, and almost awe. “Now, the rest of us looked right at them impressions in the mud. We saw they’d been made by a human hand, of course, cause there ain’t any monkeys around here besides Davy; but not one of us went any deeper. Why, after you’ve been shown, it stands out there like a mountain, and you see it as plain as you see your nose when you shut one eye. I wisht I could discover things that way; there’d be heaps of things I’d find out, let me tell you.”

“Yes,” said Giraffe, severely, as he moved away from the vicinity of Bumpus, his nose elevated at an angle of forty-five degrees; “but what we’re all hoping most for now is that you’ll hurry and get over that cold in your head, so that your natural sense of smell will come back; for then you’d certain sure duck out of that grimy old suit that’s just greased from top to bottom, and give us a chance to breathe the pure air.”

Bumpus looked at him pityingly.

“You do love to carry on a joke to the limit, Giraffe,” he said, simply.

“Joke?” burst out the other in a vociferous voice; “let me tell you, this is a mighty serious matter; and if it keeps along, some of us in desperation may be tempted to jump on you while you sleep, and make the change ourselves. We’re getting to a point where self-preservation is the first law of Nature.”

“Bah! who’s afraid?” retorted Bumpus, with a shrug of his plump shoulders; “but you want to keep your hands off me, for I’ll kick and bite like fun if set on. I know you’re just trying to see if you can’t convince me against my own good sense. This atmosphere seems all right to me; though I admit I don’t just like the looks of this black swamp water, and the ooze we meet up with sometimes.”

Giraffe gave him a last piercing look; then as if making up his mind that the case was utterly hopeless, he shook his head and turned away; while Bumpus went back to his camp duties as blithely as though care sat lightly on his head.

After they had finished breakfast the tents were struck, folded in as small a compass as possible, and one stowed away in each of the boats. Afterwards they cleaned up the camp, and made sure that nothing worth while was left.

There had been certain portions of the razorback that they did not mean to take along with them. Seeing Bumpus busily engaged Thad approached, asking:

“What are you up to here, old fellow? Just as I thought, trying to do a little favor for that wretch of a three-fingered coon, by tying up this meat where the animals will have a hard time getting at it. Yes, you guessed right that time, for the chances are he’ll come back here as soon as he knows we’ve gone, in the hopes of picking up some scraps we’ve tossed aside. Bumpus, you’re improving, because that shows you figured it all out, and hit the bull’s-eye in the bargain.”

The fat scout looked immensely pleased to hear Thad talk in this strain.

“Well, after eating such a jolly breakfast myself, it struck me as pretty sad we should be so near a miserable human being who was almost starved. No matter if he is a bad man, and deserves all he’s getting, he’s made like us, and I just reckon the lot of us would be quite as tough as he is if we’d never had the benefit of a nice home and education and full stomachs. And so I thought, as he’d be likely to come here, I’d save these pieces from the cats and skunks for him.”